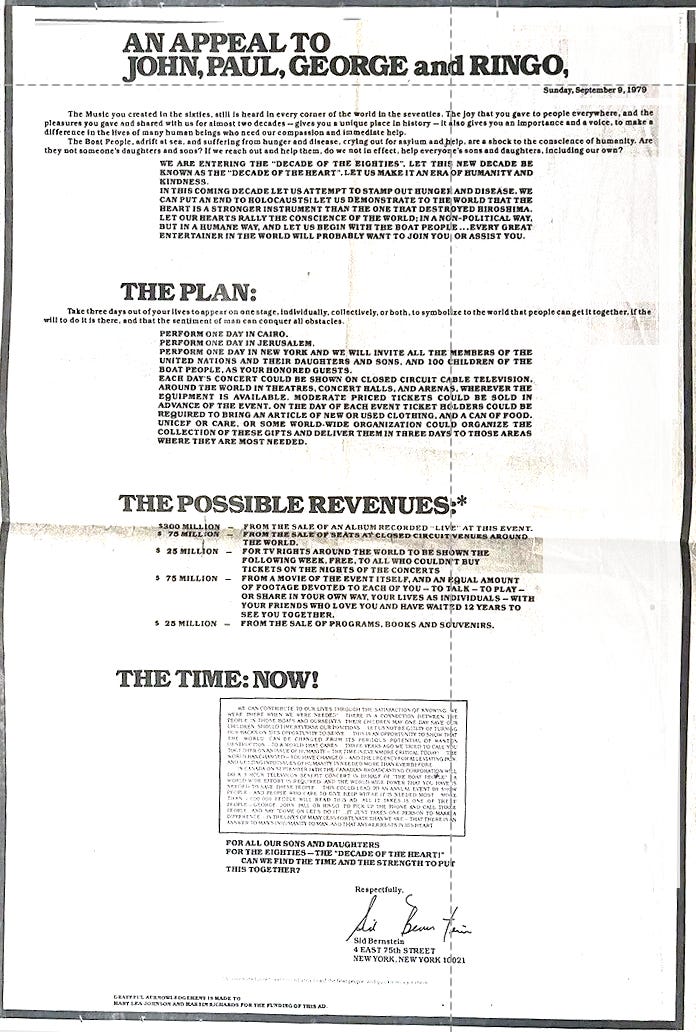

Back in 1976, a music promoter offered $230 million to the former members of the Beatles, if they would reunite for a concert. He didn’t know how to contact them—so he took out a full-page ad in the New York Times. How did the Beatles respond? Somebody tracked down Ringo, and asked if he saw the ad. “It was too long to read,” the drummer replied. As far as I can tell, none of the other band members even bothered to comment. Money couldn’t buy the Beatles back then—not even $230 million. (That’s the equivalent of $1.2 billion today.) If you want to support my work, consider taking out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).This all changed in 1987, when the Beatles song “Revolution” showed up on a Nike TV commercial. The sellout here, however, was Michael Jackson—who owned Beatles publishing rights, and cut a deal for $500,000. A generational shift had taken place by then. Michael Jackson had no qualms about endorsing brands and corporations. But there was a heavy price to pay—these sponsorships may actually have contributed to his early death. The Beatles had a very different attitude toward licensing deals, and actually filed a lawsuit in protest. The dispute was settled out of court two years later—the terms undisclosed.  But a precedent was established. Beatles songs were now available for commercial use. Sooner or later, all the big rock stars from that era swallowed their pride, and sold out. The Rolling Stones refused to let Snickers use “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” to advertise candy bars—until the offer reached $4 million. That was too sweet to leave on the table. But the ultimate cringe moment took place at the launch event for Microsoft Windows 95—where the worst dancing in history was accompanied by Mick Jagger singing “Start Me Up.” Rock and roll will never die—or so the saying goes. But it came close on August 24, 1995.  There was heavy irony in many of these deals. Consider the case of Bob Dylan—who joked, back in 1965, that he if he ever sold out for a commercial, it would be for “ladies garments.”  And 42 years later, he did just that—when his music appeared in a commercial for Victoria’s Secret.  By this time, nobody got shocked anymore when rockers shilled products. Many older fans, however, were still disgusted—how much money do Dylan and Jagger really need? Isn’t it enough just being a rock star? Marketeers feared a backlash. An article in AdWeek in 1985 warned that baby boomers had a “deep-rooted suspicion of the corporate sell,” and in 1988 Neil Young even wrote a song mocking the use of rock music in advertising.

The music video for the song, “This Note’s for You,” begins with a parody of a Budweiser commercial. It got banned from MTV for ridiculing advertisers. But the backlash never actually happened. And licensed songs started showing up everywhere. Rappers led the way. The frequent mention of consumer brand names in hip-hop lyrics had made their songs an obvious source for TV commercials. At first, companies were caught by surprise. Execs for Adidas were dumbfounded when they attended a Run DMC concert at Madison Square Garden, and saw fans lifting their sneakers up in the air during the song “My Adidas”—which mentions their brand 20 times in less than three minutes. This was better than advertising.  Companies now fell in love with hip-hop—funneling huge amounts of money to artists who would rap about their brands. They succeeded magnificently. A survey of rap music videos released between 1995 and 2008 found that more than 90% mention branded products. Companies fought like horny groupies over the hottest musicians—and bragged about their scores. “At least eight of the top twenty Billboard hip-hop singles [in 2003] referred to Pepsi” notes Timothy Taylor in his book The Sounds of Capitalism. But McDonald’s got jealous, and tried to generate similar product placement in 2005. The company allegedly paid from one to five dollars every time a song was played on the radio, if the lyrics mentioned the hamburger chain. This, of course, could backfire. Wrigley used Chris Brown’s 2008 hit “Forever” to sell chewing gum—but had to pull the ad after the singer got arrested for assaulting his girlfriend. Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs is a more recent example. In the aftermath of his arrest for excessive and abusive diddying, he was dropped by pretty much everybody. But corporations are willing to run that risk. If you want to be edgy, sometimes you get cut. After Pepsi’s huge success, the advertising business literally started merging into the music industry. In 2008,Sony BMG actually opened an in-house advertising agency. A few months later, the ad agency Euro RSCG acquired a record label. Many managers now advised artists to put advertising placement ahead of all other ways of promoting songs—because a TV commercial launches a song more widely than radio airplay. In a total reversal of previous practices, the song starts out as an advertising jingle first, and turns into a hit later. Marketing would now swallow music whole—so much so, that the top earning recording artists in the world now make more from branding deals than music. Taylor Swift recently reversed that trend—actually rising to the top of the Forbes list of wealthy musicians by live performances. But she is a rarity in the current moment. Even the most famous musicians of our day can earn more from cosmetics, or sneakers, or booze, than from a hit song. Pundits now laugh at accusations of selling out. A recent article accused ‘purists’ of holding views that are “obsolete and a little naïve.” Anyone in the music world who disagrees is attacked for “self-righteousness.” But is it really that simple? Is music just about chasing the money? That just doesn’t feel right. When music by the Velvet Underground shows up on an Expedia TV commercial, my immediate reaction is Gag me with a Warhol banana. When I see a Sex Pistols credit card I’m tempted to default on my next payment. But this isn’t just a matter of feelings—or nostalgia for a groovier day when the world ran on peace and love, not dollars and cents. There’s a very good reason why you shouldn’t sell out. People lose trust in you when you put money ahead of your values. This is true for every profession, not just musicians. Do you want your doctor to sell out? Do you want her financial adviser to sell out? Do you want your spouse to sell out? Do you want anybody you rely on to sellout? Nope. That’s why I don’t put advertising in my articles, or seek sponsors or do paid endorsements. (I sometimes offer free endorsements, when I believe in something—but I don’t take cash for it.) By the way, I also refuse all free trips to music festivals in exchange for review articles. I won’t take any cash for coverage of any sort, no matter how carefully they try to position it. [“It’s not a bribe, Ted—let’s just say it’s an honorarium.”] I refuse these things because my whole career is built on a foundation of trust. It’s a mistake to jeopardize that. Even more to the point, I don’t want to. I wouldn’t enjoy my vocation if I took payouts from the highest bidder in exchange for services rendered. I don’t think my readers would either. That’s why selling out will never be totally legit. Trust never goes out of style. Right now, there’s a crisis of trust in society. It is literally the scarcest thing in the world. That’s not unconnected to the prevalent view that it’s okay to take the money and run. The way to repair trust is by putting people ahead of cash. Musicians aren’t the only guilty parties here—and, in fact, they do very little harm compared to others who receive corporate payouts. But musicians are the right people to set an example. Maybe if superstar performers had higher priorities than their next branding deal, others might follow along. Let’s at least try it, and find out.

Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy The Honest Broker, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

Should We Get Angry When Artists Sell Out?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

When Bad People Make Good Art

I offer six guidelines on cancel culture ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment