The story of how I became a strategy consultant is shameful. I was a student at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business, and needed a job after graduation. I wanted to work in the music or entertainment industries—but I soon learned this was an impossible dream. They didn’t want me. And they didn’t want my classmates either. Hundreds of companies came to our business school to recruit talent, and they included most of the leading US corporations. So I talked with everybody—Coca Cola, Morgan Stanley, Atari, Procter & Gamble, you name it. But no record label or movie studio ever showed up. They didn’t even send job listings. Can you guess why? The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.I asked around on campus and was told the following (off the record):

I’ve never shared that story before—because I know how people inside the music business hate hearing it. And maybe it’s not a fair story. All I can say is that I found this advice very helpful. I stopped planning on a career in the music business. And I also developed a very useful theory to explain why record labels are so bad at making strategic decisions. I call it the “Idiot Nephew Theory”:

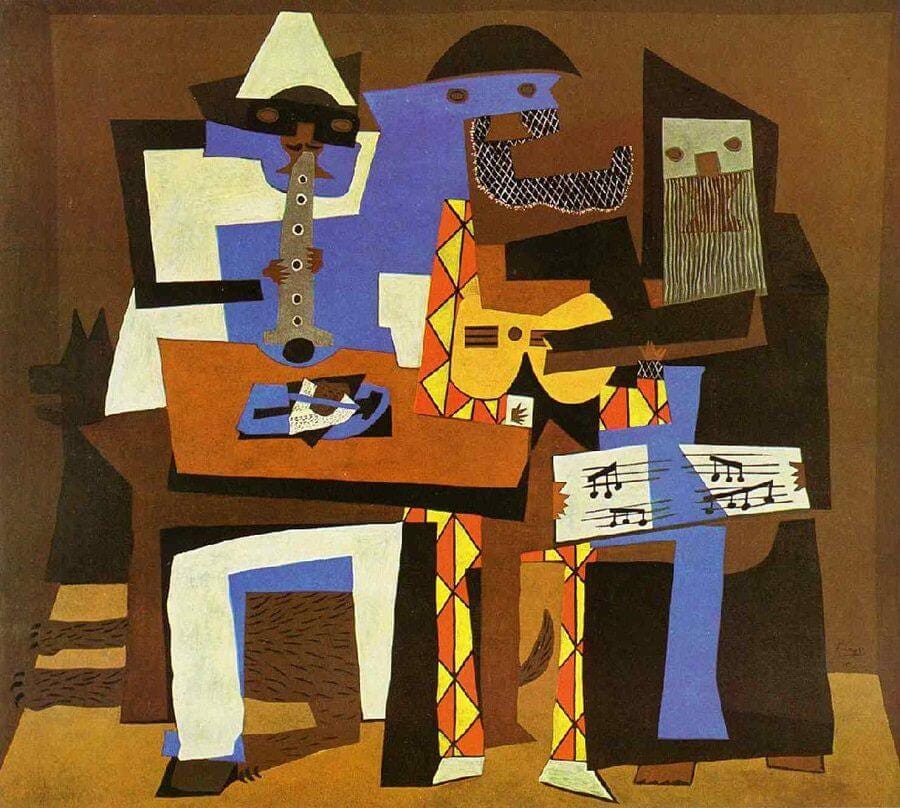

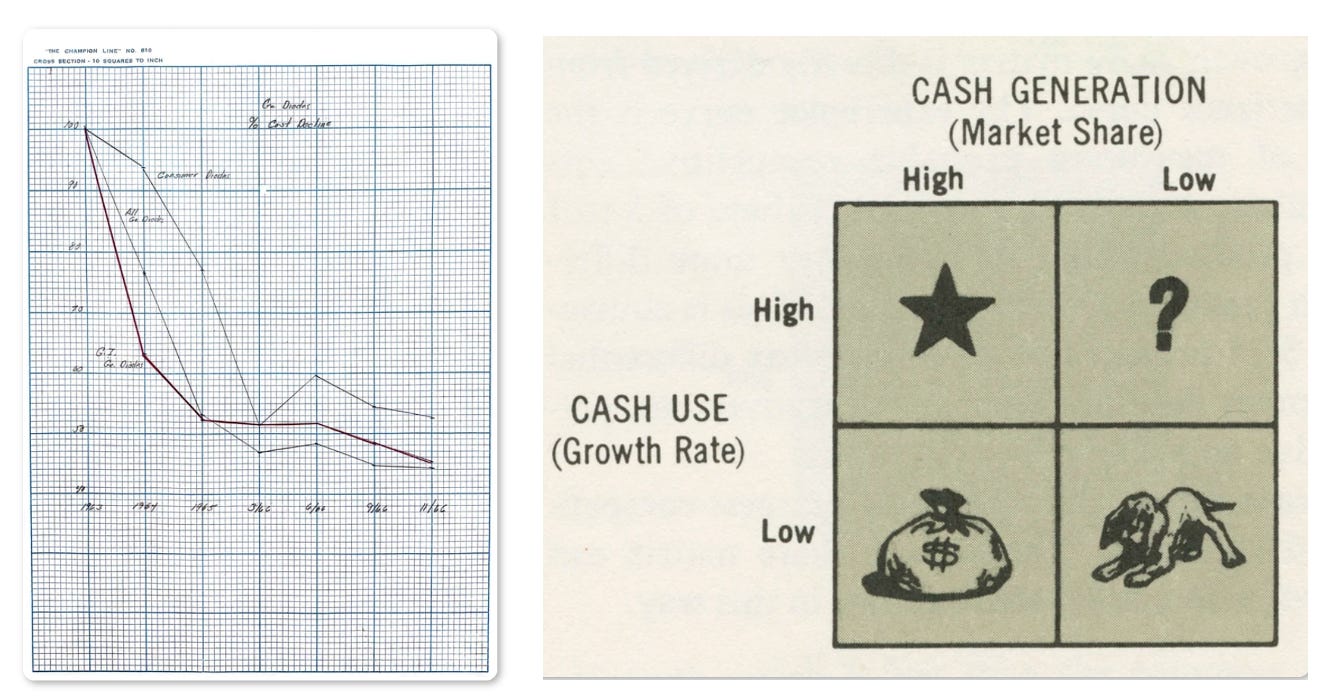

And what does the idiot nephew decide? That’s easy—they always do whatever the company lawyer recommends. Maybe this theory is wrong. All I can say is that it helps me predict events in the entertainment industry with a surprising degree of accuracy. I always operate on the assumption that there’s no business strategy in the music or movie business—only legal maneuvering. Years later, when the music business got totally reamed by tech companies—a phase we’re still living through, by the way—I wasn’t surprised in the least. The record labels respond to every new music technology by litigating, but whenever they encounter a company with more legal clout than them (Apple or Google/YouTube, for example), they simply gave up. In the future, you can test this theory yourself. You will see that it possesses great explanatory power. Back in my student days, someone told me the story of a Stanford MBA who had graduated a few years before me. His childhood dream was to work for the Disney Corporation. He kept trying to get an interview for a job there—writing letters and cold calling—and was constantly rejected. But he was so persistent that, after months and months, he finally got hired in the finance department. I’m told that the level of financial incompetence he encountered was so extreme that he could hardly believe it. Even as a junior employee he made huge improvements in their banking arrangements and cash management. I can’t confirm that story—I got it second-hand. But it rings true. Hollywood was run on nepotism, and so, of course, the financing would be dodgy. Hey, that made me feel better. But I still needed a job. Even though I knew record labels and movie studios didn’t want me, I found it hard to give up my dreams. I started hanging out at the offices of Palo Alto Records, a jazz label backed (I was told) by the guy who invented the money market fund. The label was run by Dr. Herb Wong and Al Evers, and I tried to convince them to hire me. I honestly didn’t care how much they paid. I just wanted a chance to work in a field I loved. But it didn’t pan out. (And that was probably a blessing, because the label didn’t last long.) So I started looking at other options. Management consulting firms approached me. This surprised me—I’d never seen myself doing that kind of work. But the consulting firms had more confidence in my skills than I did myself. And after my frustrations with the music businesses, it felt nice to get recruited. But what did I know about consulting? Absolutely nothing. I need to emphasize that I had entered business school without any meaningful work experience. It’s a miracle they even let me in. And maybe even more of a miracle that I survived and earned a MBA. (I’ve written about that here.) Even after all those business courses, I still thought like a musician. And—here’s the strangest part of the story—that obsession with music is why I decided I wanted to work with the Boston Consulting Group. BCG sent me a recruiting brochure about the firm. And the brochure had a reproduction of Picasso’s painting Three Musicians on the cover. I made my decision to become a strategy consultant on the basis of that picture. Here it is: I know what you’re thinking—what kind of idiot picks a job based on the cover photo in a recruiting brochure? That idiot is me. I assumed that the people at the Boston Consulting Group must be very cool and forward looking if they picked Three Musicians for the cover. Only years later did I realize that some outside design firm had probably made this decision. By then it was too late. I was already a strategy consultant. But I never regretted my decision—although I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I’d just moved to Hollywood and started knocking on doors of record labels in search of a job. The plain truth is that I’ve always acted spontaneously—and not just when confronted by Picasso paintings. Somehow it all works out. I married my wife after only spending a few days in her company, and we’re still going strong after 32 years. Many of the biggest decisions in my life got made after deliberating a few minutes—or maybe not even that much. Frankly, I don’t think my situation is so unusual. All of us are guided by feelings and impulses, and not just brute logic and rationalism. I’m probably more impulsive and spontaneous than most people because of my jazz obsession, but we all need at least a little dose of jazzy risk-taking in our lives. Of course, I still had a lot to learn in this new role. The Boston Consulting Group was very different in those days. Frankly, a lot of what BCG does nowadays makes me uneasy—I don’t think I would fit in with its ideology today. But back when I joined, it was tiny. The firm only had 340 consultants in the entire world—by comparison, it has more than 10,000 professionals today! Back then, you could know everybody by name, and they were impressive, freewheeling folks. That world is gone now. In those early days of strategy consulting, there was no bureaucracy. It was more like a musical group. (In fact, we had an actual rock band at the firm.) Risk-taking was encouraged; high quality conceptual thinking and big, bold ideas were rewarded. We were free to draw on any tool that might produce results—game theory, Monte Carlo simulations, private detective work, even drawing pictures. For my part, I found a place where I could fit in—and without sacrificing my individuality or creativity. That’s never easy to do. I wasn’t at BCG for long—I eventually left to teach jazz at Stanford—but I learned a lot during that period and still draw on it today. (I will write more about that later.) So I have Picasso to thank for all this. He’s better at career advice than you think. Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy The Honest Broker, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

How Picasso Turned Me into a Strategy Consultant

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

I Quit AeroMedLab

Watch now (2 mins) | Today is my last day at AeroMedLab ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment