Back in 1996, critic Susan Sontag warned that seriousness was disappearing from society. She feared that the inherent laziness of consumerism was now permeating everything. Anything tough or demanding was bad for business And everything had been turned into a business—even intangibles like education and human flourishing.

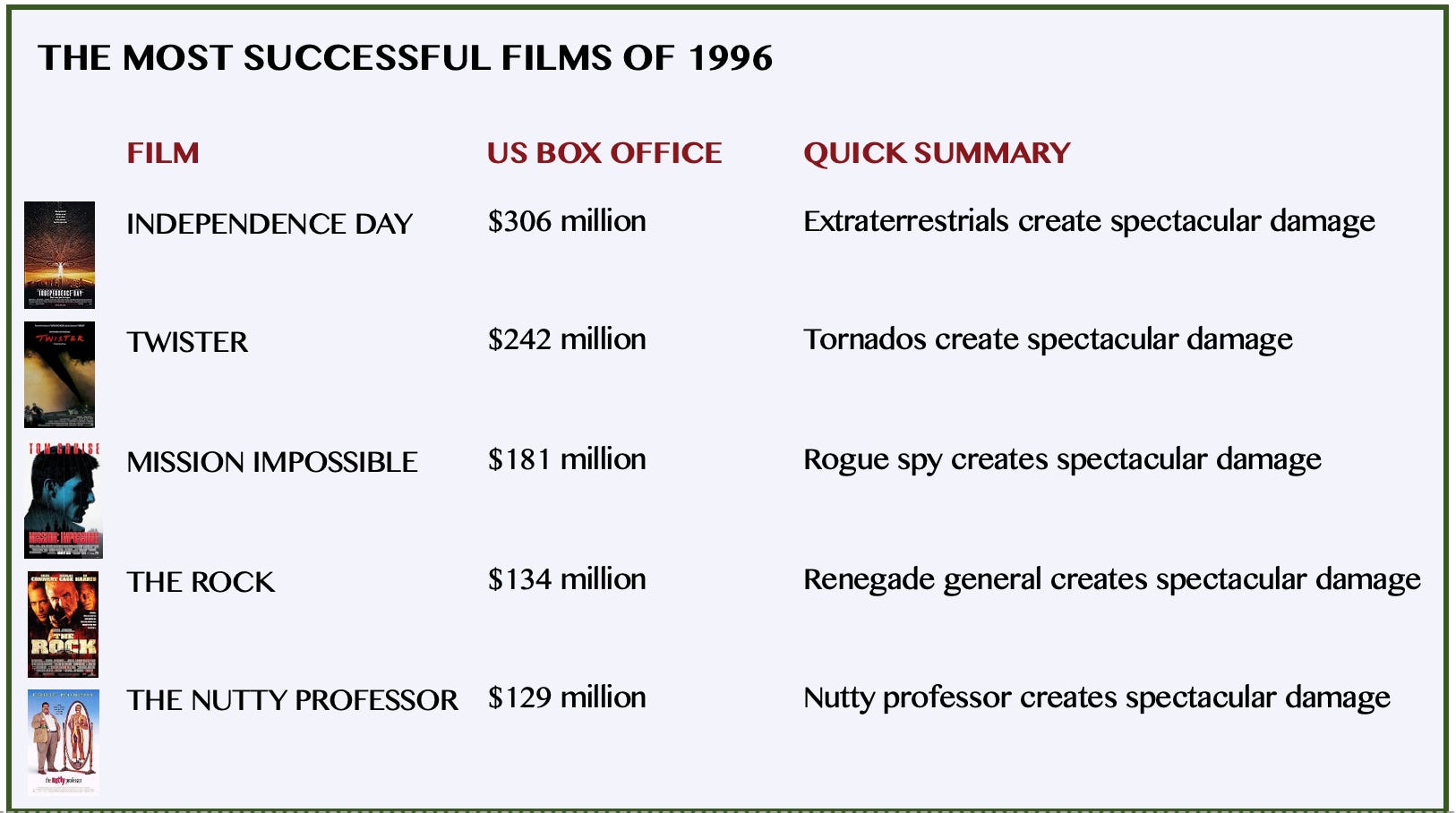

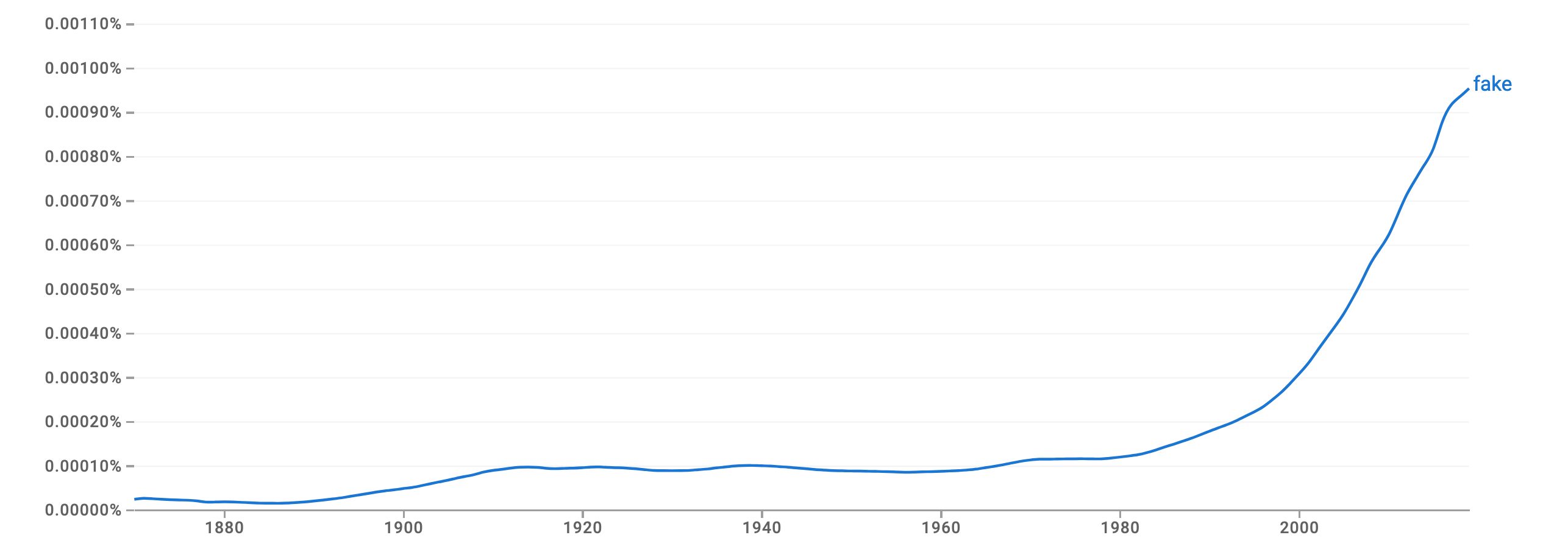

“The undermining of standards of seriousness is almost complete,” she declared, “with the ascendancy of a culture whose most intelligible, persuasive values are drawn from the entertainment industries.” In this frivolous new world, everything must be pleasing and inoffensive. Everything and everybody gets marketed like an exciting new product—even old, creepy politicians, or ancient film actors, or 80-year-old rock stars. They all get repackaged and rebranded—thank the digital gods for those apps that make old stuff look new! Everything is now easy to digest and suitable for mass consumption. The public accepts this as a matter of course. They hardly expect anything to be real nowadays. Let’s stay with 1996 for a moment—because it was a turning point. Before that time, Susan Sontag had been very receptive to popular culture—movies, commercial music, and campy pop art. But each of these was becoming unrecognizable in their turn-of-the-century guises. Consider the movies. A quarter of a century before Sontag offered this assessment, movie theaters showcased the gritty, risk-taking of The Godfather, Chinatown, Taxi Driver, and Raging Bull, and all those artsy foreign movies that Sontag loved. But that was ancient history by 1996. Here’s a thumbnail sketch of the top grossing films of that year. There’s not much here to take seriously. These films were all different—but they had one thing in common: spectacular special effects. In the final years of the twentieth century, computer technology had reached a level where massive levels of destruction could be shown on screen with an immediacy never before possible. Technology was setting the agenda for creativity. Everything else—script, directing, acting, was subservient to the computer-generated imagery. But 1996 was just the beginning of cinema as a digital spectacle. With each passing year, the artificial digital component has increased, and the real human element decreased. The advent of AI will now accelerate this even further. We may soon reach the point where nothing on the screen is real. Does it matter? If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).I’m reminded of culture critic Thomas Carlyle’s mockery of the thought leaders behind the French Revolution. They churned out 133 different newspapers in Paris back then, filled with rumors and bravado—but very few facts. These 133 newspapers all had different agendas, built on the dreams and fantasies of journalists—who were proven painfully wrong again and again. Carlyle rightly mocks the citizens of France who, in those days, put so much trust in paper—whether the deceptive newspapers or the collapsing paper currency. Humans had once created a Stone Age and an Iron Age—but now settled for the Age of Paper. The hot air paper balloons, so popular in Paris in those days, were emblematic of the new attitude—they stayed aloft a few minutes and then crashed to the ground. The paper journals and paper money didn’t last much longer. By implication, we live today in a digital age—or the Age of Less-Than-Paper. It doesn’t help that that cutting edge technologies are focused so much on deception—fake images, fake video, fake audio, fake books by fake authors, fake songs by fake musicians, fake news, fake everything. Here’s the Google analysis of the use of the word fake in texts over the last 150 years. Fake is our leading candidate for word of the century. It captures almost everything relevant now in a single syllable. You have to give Susan Sontag some credit, the inflection point in accelerating fakeness happened almost exactly when she complained about the collapse in seriousness in the mid-1990s. Here’s the scariest part of the story: Most of this is by design. Our culture is now obsessed with deception and misdirection—and it’s not just on the movie screen anymore. You see it everywhere, from cosplay conventions to bands wearing masks to the misguided virtual reality mania. Lifestyles are increasingly about pretending. Your real self stays in hiding, while your fake self gets presented in the most spectacular way on social media and other digital platforms.

Never before in history has authenticity been in such short supply. That’s so much the case, that the very word authenticity is mocked. (I will write about that more in the future.) I know people who get angry just from hearing the word authenticity. They insist it doesn’t exist. It never existed. It can’t possibly exist. And maybe in their lives, as digitally constructed, it doesn’t. This is the flip side of our culture of artificiality. Anything that threatens the dominant fakeness with reality stirs up an intense backlash. The dreamer does not want to awaken from the dream. So are you surprised that everything in culture has a feeling of unreality right now? It’s like cotton candy that shrinks to nothing as soon as you put it in your mouth, just leaving a brief sickly sweet taste. Can you build a culture on cotton candy? We will soon find out. In a cotton candy society, everything feels insubstantial:

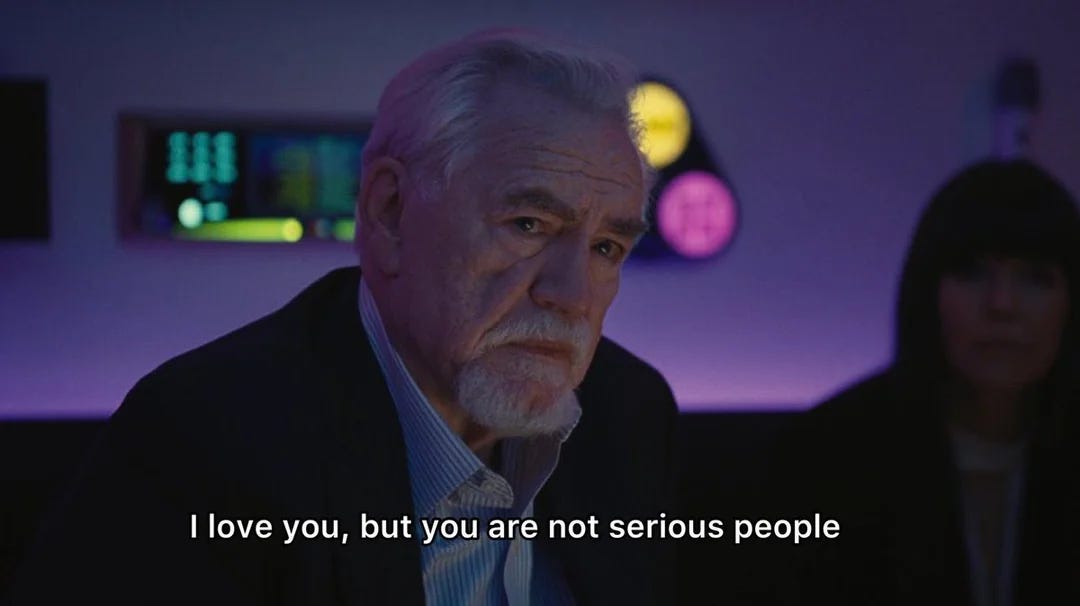

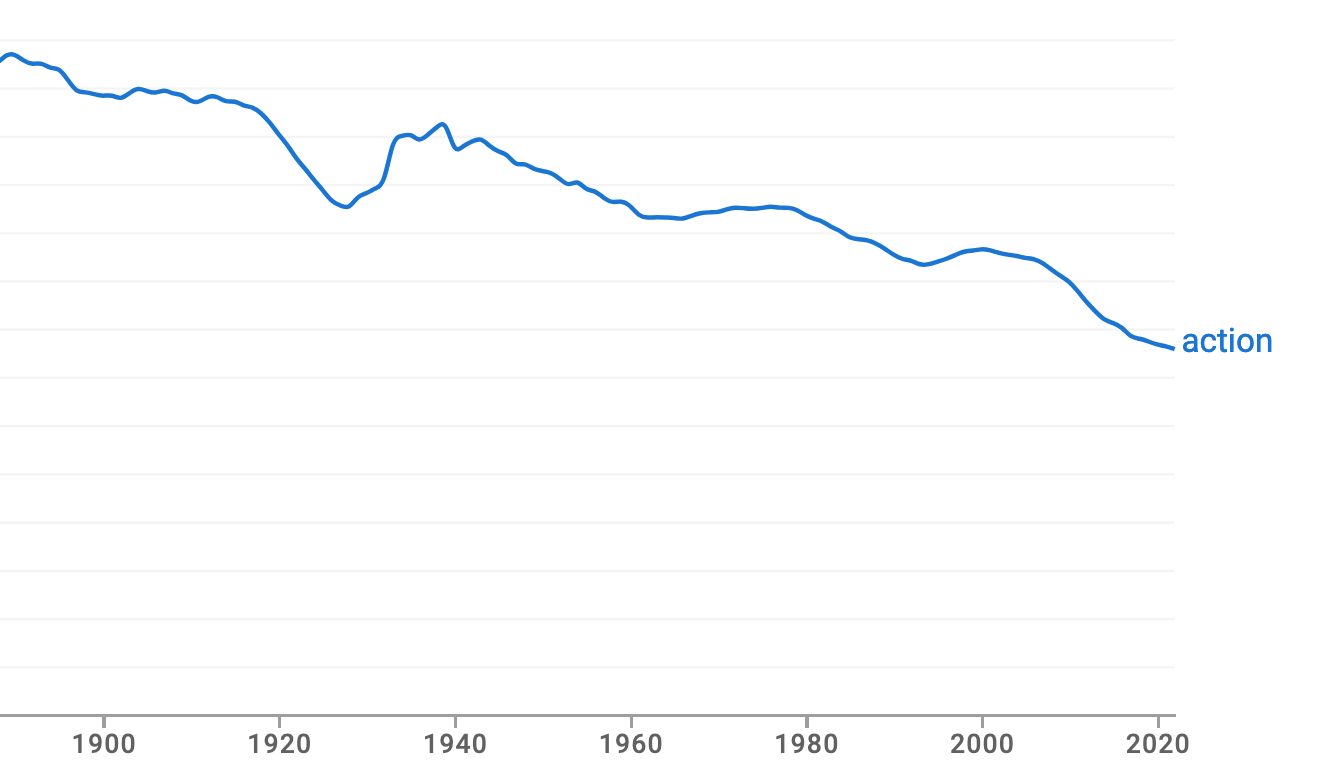

These are all signs that we are living in a society running low on seriousness. And even when conflicts move into the real world, the combatants still betray their lack of seriousness. This is more than just my verdict on an election season that was served up in carefully scripted images, videos, and soundbites. The larger truth is that we are living in a time when all disputes and engagements take on this fabricated quality. Instead of doing something tangible or constructive or even persuasive, instigators work to create a meme—consider, for example, the project of hurling tomato soup at famous paintings, or staging campy protests that look like performance art. Compare these initiatives to what happened at Selma or Normandy or other centers of brave resistance in an earlier day. If an era is defined by its battlegrounds, we have little to brag about.  Is a single person in the world persuaded by these interventions? Or do they discredit the very organizations that view them as a convincing substitute for action? Ah, the word action. That’s fallen out of favor, too—another symptom worth noting. Here’s the Google analysis of its usage since the year 1900. The decline in the word action accelerated during the same period that saw the rise (shown above) in the word fake. They are mirror images of the same cultural shift. Participants at Normandy and Selma were taking action. But soup hurlers operate at a symbolic level, or (let’s be honest) a less-than-symbolic level—because these paintings have no connection in any way with the issues at stake. The targeted paintings aren’t appropriate symbols of the evil they are supposed to represent. In fact, they embody the exact opposite. A psychoanalyst would say that the hostility here is displaced—like people who kick the dog because they hate their boss. It’s not mere coincidence that anger and violence are targeted at objects that are inescapably

In an age of fakery, people who operate without seriousness will inevitably focus their hostility on precisely these cherished objects. Now consider the case of Apple, which recently released a commercial showing real-world creative tools getting squeezed and crushed—until they turn into a tiny digital device. Apple though this was very clever, and was shocked when people expressed their disgust.  The backlash was intense. Apple turned off comments on the video, and then rushed to issue a formal apology. But the cluelessness in Cupertino is understandable. The dominant companies in Silicon Valley are threatened by reality and seriousness—which are like Kryptonite to the digital agenda. So these mishaps are inevitable. Fakery is now a business model. Reality is its hated competitor. But all things happen in cycles. And even this crisis of seriousness will reverse. I already hear rumblings—of discontent with all those fake things listed above. It’s actually more than rumblings. It’s rising to a roar. Gift subscriptions to The Honest Broker are now available.Most people really do dislike fake news. They are sickened by fake songs by fake musicians. They are burnt out by the fake online wars, and all the rest. Even those spectacle-driven fake films with their computer-generated effects are now dying at the box office. And here’s the most salient fact of all: People who have their act together are now taking things very seriously in there own lives. They aren't waiting for guidance from an app from the Apple Store or a post from an influencer. They’re taking charge on their own initiative. I see them everywhere. And in the aftermath of the election—where everything was stage-managed and curated to the utmost degree—I expect to see still more of them. These serious people are the real deal, and don’t have time for fluff. They are already detaching themselves from the businesses and institutions that dish out cotton candy culture. They will be the new influencers—but don’t expect them to use that degraded word. From their perspective, they will be replacing influencer culture with something much, much stronger. Or better yet, let’s call them leaders—because that’s what they will be. And that’s such a better word than influencer. These tough-minded individuals will eventually set the tone for more serious engagement throughout society. This is inevitable—and betting against it is a sucker’s wager. All the fake AI and virtual reality and gimmicky digital tricks in the world won’t stop it. In fact, my hunch is that the more the tech world serves up their puerile fakery, the more they will accelerate this return to seriousness. That’s because there’s a hunger for honest human engagement that fakery cannot satiate. This hunger will be fed, sooner or later—and probably sooner. Five years from now, the cultural landscape will look much different. I expect a lot will change in just the next 12 months. If they were wise, the tech innovators would join us in building a new age of seriousness. But that hardly matters, because we won’t be waiting for their permission. COMING SOON: I will write about “How to Become a Serious Person.” You're currently a free subscriber to The Honest Broker. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

Is There a Crisis of Seriousness?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Top 3 UX Design Articles of 2024 to Remember

Based on most subscriptions ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment