When I was in college, I competed in various quiz competitions. These were elaborate intercollegiate affairs with buzzers, moderators, judges, and all the other paraphernalia of a TV game show. These matchups were no joke, demanding not only knowledge, but quick recall and fast reaction time. In my shining moment, I even appeared on network television, as part of a team that defeated Yale for a national championship. I would have gone pro, if there had been a pro to go to. If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).As it turned out, this became a tradition in our family. The only difference between us and the Manning clan, is that they play quarterback, and makes tens of millions of dollars. But who’s counting? So, more recently, my son Thomas participated in similar events, and served as captain of a high school team that won a US title. He continued to compete in college, where his team came within one question of winning the national championship. My nephew, also named Ted, made his mark in these same academic competitions during his college days, gaining some lasting renown among the insiders who follow such things. The curious satisfaction for all of us is that our specialty in these contests is invariably arts and humanities—that’s also a family tradition—and those are the very fields where head-to-head competitions with objective scores are almost non-existent. That’s what made these contests so much fun for us.

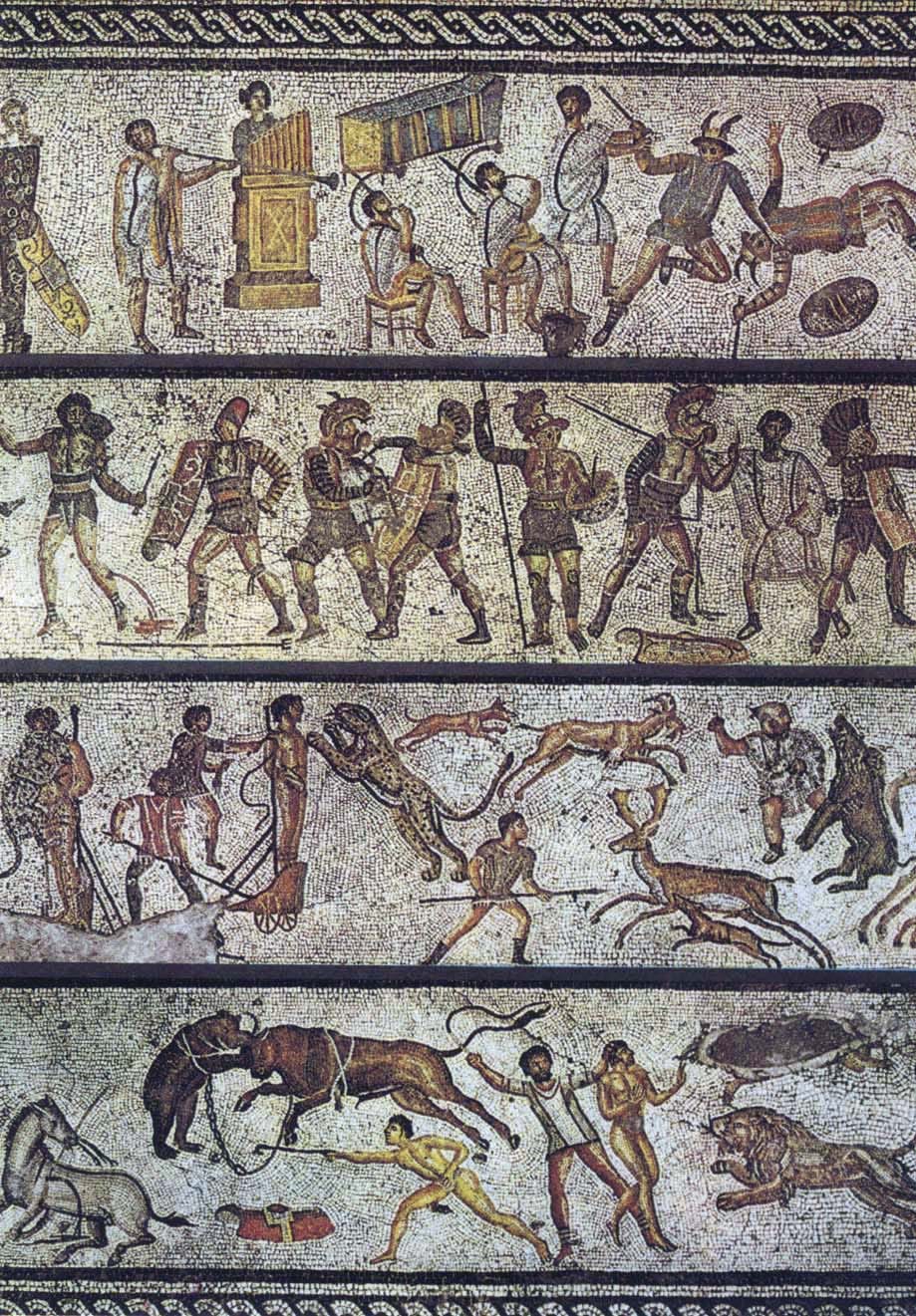

There’s a peculiar enjoyment for a humanist, in matching up with peers at Ivy League schools, and seeing if you can beat them to the buzzer, so to speak. These contests, now a distant memory from my youth, are the only times in my life when I competed in a genuine matchup in the world of arts and culture with results tabulated in real-time competitions on the basis of objective standards. I know that a career in the arts can’t really be like that. But I was lucky to get a taste of it, and can’t help envying professions where performance isn’t such a subjective affair, but can be measured with such confidence and precision. Chess players always know where they rank, and exactly what they need to do to move up in the hierarchy. The same is true of sales people who earn their bonuses based on the numbers. Or TV producers who can check out the morning-after ratings. Or even the adolescent who is battling with buddies in a video game. I sometimes wish the life of a creative professional were more like that, if only for the clarity it provides. But even I realize how strange it gets when actually applied in practice. Just look at all the “best of” lists in music and books, and all the arguments that ensue. And there’s no stranger example than the Olympic competitions for artists. If you haven’t heard of these contests, I’m not surprised. Hardly anyone mentions them anymore. But arts were part of the Olympics for forty years, from 1912 to 1952. Although the idea of artists competing for gold medals may seem bizarre, the practice actually goes back to the ancient Olympics. Sports competitions in ancient Greece always involved music. Sometimes it was integrated into the athletic competitions. The Greeks, for example, believed the long jump required music in order to optimize the rhythmic coordination of the competitors. In other instances, the music served to entertain or organize the crowd at ancient competitions. But the most unusual situation involved actual music contests, treated as quasi-athletic events. Ancient sources tell us that Herodorus of Megara gained renown as champion in ten separate Olympic competitions. But he wasn’t an athlete, he was a trumpeter. Ancient sources tell us that he could play two trumpets at once, a feat that allegedly inspired Macedonian troops during the siege of Argos in 303 BC. Adding to the incongruity, Herodorus looked the exact opposite of an Olympic medalist. He was almost as famous for his eating and drinking as he was for his music—at a single sitting he could consume seven kilos of meat and an equal amount of bread, washing it down with six liters of wine. His enormous body may, however, have helped him blow those loud trumpet notes that earned him Olympic victories again and again. Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, was well aware of these precedents, and wanted to include the arts in his competitions. In fact, he envisioned the arts as a key ingredient in the modern Olympic games—and for the plausible reason that they would elevate the international event he was envisioning above all other such competitions. “There is only one difference between our Olympiads and plain sporting championships,” he declared, “and it is precisely the contests of art as they existed in the Olympiads of Ancient Greece, where sport exhibitions walked in equality with artistic exhibitions.” But the local organizers of the early modern Olympics were not convinced. So there were no arts competitions in Athens (1896), Paris (1900), or St. Louis (1904). Finally, a plan for integrating the arts into the games was approved for the 1908 Olympics, originally planned for Rome; but when the event moved to London because of financial troubles due to the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, the arts were again put on hold. The Baron did not abandon his plan, and pushed for arts competitions at the 1912 Stockholm games. The Swedes initially resisted, but finally agreed—although insisting that the artistic works submitted had to have some thematic connection to sports. Only a few artists participated, but medals were awarded in five categories. The gold medal in music went to Italian Riccardo Barthelemy—whose day gig was accompanying famous opera singer Enrico Caruso—for his “Olympic Triumphal March.” The high point of the Olympics art competition happened in Los Angeles in 1932. An exhibition of submitted works took place at the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art, and drew almost 400,000 visitors. That’s far more people than can fit into the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum (which, in 2028, will become the first stadium to host three different Olympics). The arts medals were eliminated after 1948, but for the worst of all reasons. The modern Olympics originally focused on amateur competitors—with professional athletes disqualified from participation—but most of the artists involved were professionals. According to critics, this undermined the integrity of the event. What a joke that is. Just imagine—painters and composers make too much money to compete alongside athletes. In later years, artistic exhibitions were sometimes associated with the Olympics, but the days of medals and competitive events were over. But it’s legitimate to ask whether they shouldn’t be brought back. In a world in which millionaire NBA players compete in these international contests, there certainly can’t be any objection to the far poorer, albeit professional, artists from participating. And there are many other benefits. Just consider how successful the Eurovision contest has been in generating cross-border music careers, and global awareness for artists who might otherwise never have a platform outside of their own nations The contest definitely creates international goodwill, and also has the benefit of being fun and entertaining. I’m not making any great claims for the caliber of the songs honored. But the purpose of such events is more than mere aesthetic refinement. And think of the other international arts awards that generate so much public interest, and help build both the audience and financial security for deserving artists. The Nobel Prize in Literature is the most obvious example, but there are many others. Once again, I’ve often criticized the actual decisions of the judges, but even the arguments they stir up are good for the culture. And for some art forms, an Olympic event might be the single best way of raising public awareness. Most people can’t tell you the name of one living sculptor or modern dance choreographer or poet. Maybe if they handed out gold medals on TV that would start to change. Perhaps the biggest obstacle to this is our inherent reluctant to treat the arts as a kind of sport, with winners and losers. And I don’t disagree with that. Although I enjoyed my own days as a arts and culture competitor in quiz contests, I don’t really believe that creative pursuits can be quantified in the same way as, say, a golf or tennis event. But that has never stopped judges from assigning quantitative scores to artists. I’ve often been enlisted as a judge for various arts organizations, and in almost every instance numeric scores are assigned to works—although those scores are rarely released to the public, just the names of the winners. Everyone knows that the numbers here are subjective, but that doesn’t mitigate the positive value of the process. So let’s give it a chance. It’s too late for the Paris Olympics, which are starting tomorrow, but Los Angeles will host the event again in four years. That give us plenty of time to prepare. So why not bring musicians, painters, dancers, poets, and all the rest to LA, alongside all those well-toned athletic bodies. It might even give a boost to ratings. And it almost certainly will give a boost to our culture. Of course, my most cherished hope is that they will add quiz competitions to the Olympics. I might even consider coming out of retirement. You're currently a free subscriber to The Honest Broker. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

When the Olympics Gave Medals to Artists

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Top 3 UX Design Articles of 2024 to Remember

Based on most subscriptions ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment