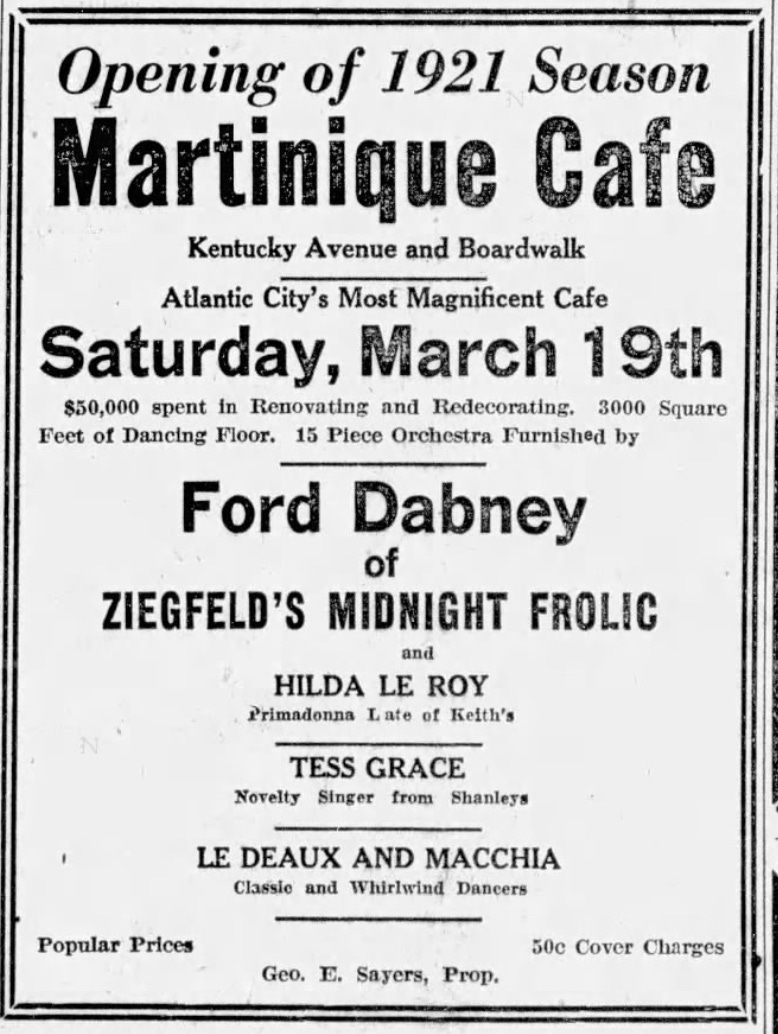

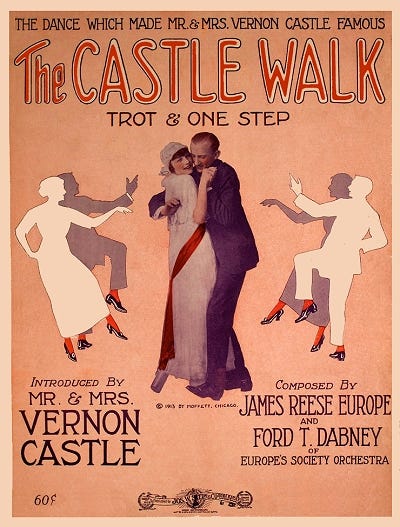

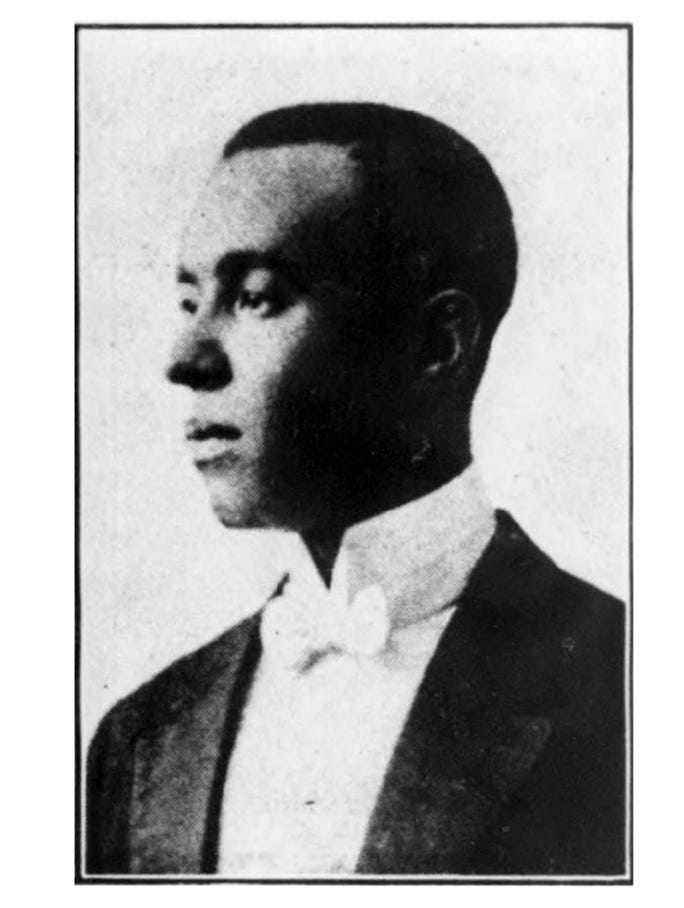

One of my favorite Wikipedia pages is devoted to “Inventors killed by their own inventions.” It’s a surprisingly long list. There are many lessons to be learned by perusing its contents. But the main one is: Don’t push into the future until the future is ready. And the worst mistake is to bet on the wrong future. If you do that, it can blow up in your face. That literally happened to some of our foolhardy inventors. Even artists can suffer if they’re born at the wrong place or time. Consider the case of Ford Dabney—a major African American composer who came of age in the years leading up to World War I. A decade later, he would have been a jazz star. But jazz didn’t exist in 1914. If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (for just $6 per month).The obvious comparison is with Duke Ellington. Both Dabney and Ellington were born in Washington DC in the late nineteenth century, and raised in supportive middle class settings where musical talent was nurtured. But Dabney was born in 1883, while Ellington was born in 1899. That was enough of difference to make Ellington a jazz star, while Dabney falls into the cracks. He learned ragtime piano in his youth, but the market for rags was already declining during his teen years. But Dabney was an extremely creative rag composer, and his works reveal his skill in pushing beyond the oom-pah rhythmic clichés of the idiom. Consider “Porto Rico” from 1910.  Or “Haytian Rag’ from that same year.  Dabney was a risk taker, and ready to make bets on the future. So when he got invited to move to Haiti in 1903 and work for the country’s president Nord Alexis—at an astounding salary of $5,000 for just four months work—he jumped at it. He ended up spending three years in Haiti. But any hopes of living as a member of the ruling class in a post-colonial society were dashed when famine and riots led to the collapse of the regime. Dabney escaped back to the US, where he had to reinvent himself. To his credit, Ford Dabney always found a way to make money. But the same thing that happened in Haiti, kept recurring in his life. He always staked bets on stability, right before an upheaval changed the rules. That was true when Dabney got involved in vaudeville, right before the rise of movie theaters took away his customers. He turned to songwriting, and wrote successful songs, but they are rarely heard today because of their minstrel conventions. His biggest hit, “Shine,” is almost never sung nowadays because listeners find its lyrics uncomfortable (although that didn’t stop Louis Armstrong from enjoying a hit with it.) The same is true of Dabney’s recordings. He led one of the great society dance bands of the era, and enjoyed a huge success with Ziegfeld Follies and backing star dancers Vernon and Irene Castle—collaborating with James Reese Europe on the music that launched the fox trot craze. Years later, a journalist for the New York Age recalled the night when Ford Dabney “made history” by taking the bandstand for Ziegfeld’s “Midnight Frolics Review” on 42nd Street. This was a high risk setting, with “all the important members of the Socialite Who’s Who of New York” in attendance. Here’s what happened:

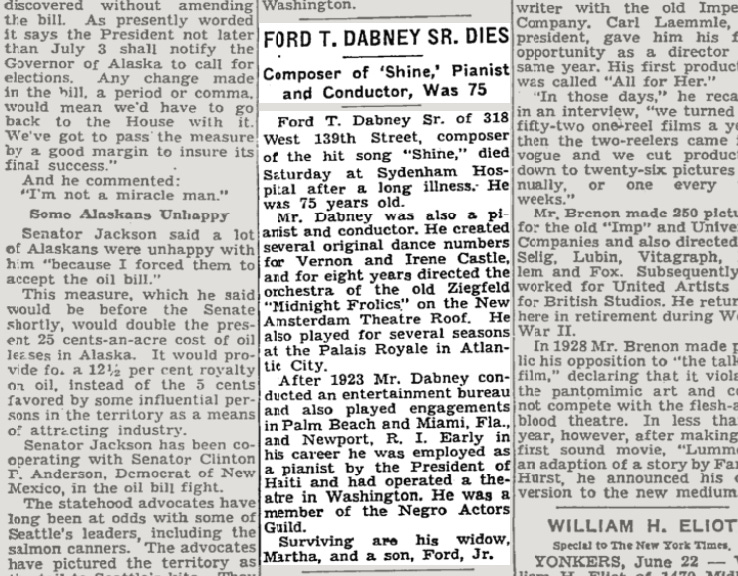

That should have been the start of Dabney’s triumphant career as a bandleader. But it’s hardly an exaggeration to say that it was downhill from this point for the brilliant young musician. Like his colleague James Reese Europe, Dabney was still loyal to the conventions of ragtime and society dancing at the very moment jazz was emerging as the hot new commercial style. If he had been a little younger, he would have probably embraced jazz with enthusiasm. And he could have been celebrated today as one of its inventors. But that wasn’t how it played out. Dabney got a chance to make records in August 1917. Just a few weeks earlier, the first jazz record “Livery Stable Blues” had become a surprise hit—but this is still an awkward topic in American music history, because that rival band was all white. Dabney could have settled the score, and asserted the primacy of African-American musicians in this new genre. But Dabney was now 34 years old, and had a reputation as an established bandleader. So he took the safer route, and recorded the songs that he performed to acclaim for Ziegfeld audiences and society dance patrons. Over a period of 30 months, he recorded around 60 tracks for Aeolian. Here Dabney demonstrated how well he understood the building blocks of jazz—danceable rhythms, syncopated melodies, bluesy chromaticism, and the like. He also anticipated the future by making one of the first commercial records featuring an integrated band. This decision to showcase white singer Arthur Fields with Ford Dabney's Syncopated Orchestra is a milestone moment in American music. But Dabney wasn’t ready to embrace the looser, more improvised sound of the emerging hot jazz bands. He probably scorned “Livery Stable Blues,” with its corny use of horns to imitate barnyard animals. Instead he wanted to elevate his ragtime sounds into a sophisticated dance music for New York elites. This was no small achievement. But it meant that Ford Dabney did not participate in the birth of jazz. In fact, he is almost totally forgotten today. His records have been difficult to find, and most books on American music history completely ignore his contributions. So even as his erstwhile collaborator James Reese Europe has enjoyed a posthumous revival in his reputation, Dabney never benefited. If he is remembered for anything, it’s for his hit song “Shine”—which is too controversial to sing. But Dabney is much more than a late-stage minstrel or failed ragtime songster. That’s why I’m so delighted that Archeophone Records has decided to release an elegant double album, containing 48 tracks by Dabney’s band, with detailed liner notes by Grammy-winning writer Tim Brooks. Finally Dabney emerges from the shadows, and returns to the limelight—after an absence of more than 100 years. The range of this music, recorded between 1917 and 1922, is impressive. Dabney can serve up hot dance numbers or spirited marches or trombone novelty tunes or sweet pop songs—all with polish and panache. During this period, blues songs caused a sensation in the music world, and on the later tracks here Dabney shows how comfortably he assimilates it into his musical vision—but adding a veneer of society sophistication suitable for the ballroom. On “Bugle Call Blues” he starts with “Reveille” and hints of other army bugle calls, before settling into the familiar 12-bar form. But before he’s done, he moves into the minor with an allusion to W.C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues.”  Five months later, the New Orleans Rhythm Kings recorded a similar number, possibly influenced by Dabney, only looser and jazzier. Their version is better known today, but Dabney was there first. Later in 1922, Dabney recorded a version of “Doo Dah Blues” which is positively jazzy. At this juncture, he just needed to add a couple of hot soloists, and Dabney would be ready to ride the great wave of musical innovation propelling the Jazz Age.  But that’s when Dabney stopped making records. Maybe he thought that jazz and blues were passing fads. Many people believed that in the early 1920s. But, in fact, the quality of recorded jazz started to improve dramatically in 1923, when Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and King Oliver made their first records. The next year, Duke Ellington entered the studio for the first time. Dabney should have been part of this—or even ahead of the trend. He was living in Harlem, just a few blocks away from the Cotton Club, where Duke Ellington would rise to fame. Yet Dabney was happy to watch other jazz stars record his best songs, but never took the trouble to do it himself. In fact, he never made a single recording of his most famous composition “Shine.” When the Jazz Age was in full swing, Dabney was in his forties, and preferred a more stable life without the hassles of touring, recording, and bandleading. He still got gigs—but instead of taking themselves, he typically worked as a booking agent for others. On the few occasions when he performed, it was usually at parties for the wealthy, often down in Palm Beach, Florida or out in Newport, Rhode Island. But Dabney didn’t need fame and acclaim. His commissions and royalties allowed him to live comfortably. But soon Ford Dabney was forgotten. As far as I can tell, he never gave a single interview to a journalist during the rest of his lifetime. Do a favor for a friend—give a gift subscription to The Honest Broker.Dabney lived until the age of 75. But when he died in 1958, the obituary in the New York Times focused almost entirely on what he had done before 1920. At the time of his death, a few New Yorkers still remembered Dabney and those glorious days of Ziegfeld’s Midnight Frolic. But not anymore. Maybe this comprehensive reissue will earn Dabney—at long last—a place in the history books. That happened with his predecessor Scott Joplin and his colleague James Reese Europe—who are both now considered major figures in American music. He eminently deserves it. And his recordings are now finally available. All it would take is for a few people to give them a listen. You're currently a free subscriber to The Honest Broker. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

He Might Have Been the First Jazz Star...

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Top 3 UX Design Articles of 2024 to Remember

Based on most subscriptions ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment