What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in 'Pulp Fiction'?Here's the latest installment of my book 'Music to Raise the Dead'—currently available only on SubstackBelow is the latest installment of my book Music to Raise the Dead. This work—currently available only on Substack—is the culmination of decades of research into the power of song as a change agent in human life. I’m publishing a new installment every few weeks. Each chapter focuses on a single question, and can be read on its own—or as part of the larger narrative of the book. Here’s the table of contents, with links to the sections already published. MUSIC TO RAISE THE DEAD: The Secret Origins of MusicologyInteractive Table of ContentsPrologue

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction? (Part 1 of 2)By Ted Gioia This book is about strange trips. This book is a strange trip. I started by analyzing an ancient Macedonian papyrus from Derveni—the oldest surviving book in Europe—which told readers how to use magical songs to survive dangerous journeys. And I’ve somehow ended up in Hollywood. But this makes perfect sense. The brand franchises of movie moguls have their roots in those magical songs of ancient heroes. The only difference is that the author of the Derveni papyrus wanted everybody to possess the magic. You can be the hero on a transformative journey. Everybody is allowed to sing these life-changing songs. Hollywood reverses all this. The hero only exists on screen, not in real life. You just sit in the audience as an observer—after buying a ticket and overpriced popcorn. The magical song is reduced to a soundtrack theme. You can listen, but you don’t sing along. Not even buying a ticket gives you that right. These are not small differences, although perhaps the mismatch here is inevitable. The heroic possibilities in human life simply don’t meet the needs of the entertainment industry. I’m reminded of a favorite passage in a David Foster Wallace story, when a burnt-out young man—he describes himself as a wastoid—is shaken out of his complacency by (of all people) an accounting professor. This teacher berates his students, demanding that they aspire to heroism—but “not heroism as you might know it from films or the tales of childhood. . . . The truth is that the heroism of your childhood entertainments was not true valor. It was theater.” Grown-ups, he continues, must learn what real heroism is. The professor goes on to define it—in a way that both unsettled and inspired me when I first read it:

The ‘wastoid protagonist eventually finds fulfillment as a Certified Public Account working for the IRS. It seems absurd—accountancy can’t offer a heroic life, no?—and Wallace knows that. But he’s also deadly serious about what he’s saying here. Even more to the point, no Hollywood studio could ever make a film out of this story, and for the very reason the professor outlines: Nobody would be entertained. All that might be fine, at least from the standpoint of the movie business. But the curious fact remains that Hollywood itself is uneasy at this state of affairs. The filmmakers know how fake their hero tales really are—and I’m not just talking about the stunts and computer generated effects. The plots and characters are bogus in every way. They struggle to make movies about the real heroism of everyday life. They recognize how unsuitable “the quiet, precise, judicious exercise of probity and care” is for the mass market—yet those are the stories that most need to be told. This creates a cognitive dissonance in pop culture. Hollywood wants to bring magic into people’s lives, but they are stuck with these superhero stick figures playacting the clichéd 12 steps of the cinematic hero’s journey. That story exhausted its potential long ago. But they don’t have another one. One sign of this exhaustion is a contrivance known as the MacGuffin. The term was invented by scriptwriter Angus MacPhail, best known for working with director Alfred Hitchcock. The MacGuffin is the object of the hero’s quest in a Hollywood movie, but MacPhail and Hitchcock realized—with brilliant insight, I must add—that any details about this central point of motivation in the story are irrelevant. The characters on the screen spend all their time worrying about this object, but the audience really doesn’t care. They enjoy the quest—especially the fights and chases, trickery and double-dealing—but it doesn’t matter if it's a lost Ark of the Covenant or a Maltese Falcon or (in the spoof spy film What’s Up, Tiger Lily?) the recipe for the best egg salad in the world. The fun is in the pursuit, not its final object. But consider the unsettling implication: Hollywood heroes are really chasing nothing. By the time we get to Pulp Fiction, the audience is invited to laugh at the emptiness of the concept. What was in the briefcase? Just a lightbulb and a battery—but all the audience gets to see is the glow. If you want something more, something truly illuminating, you won’t find it in Hollywood. “The main thing I’ve learned over the years,” Hitchcock told François Truffaut in a 1962 interview, “is that the MacGuffin is nothing.” He goes on:

In seeking the origin of this approach, Hitchcock gave credit to Rudyard Kipling, who used the device frequently in his stories. “Many of them were spy stories, and were concerned with the efforts to steal the secret plans out of a fortress. The theft of secret documents was the original MacGuffin.” But Hitchcock underestimates the lineage of this device. The MacGuffin actually dates back to the very beginnings of commercial publishing, if not earlier. Until that moment, a MacGuffin is not only worthless, but actually harmful, distracting potential heroes from their true path to mastery and enlightenment. But as soon as the hero’s journey loses its real life applicability, and gets reconfigured as a charming story to pass an idle hour, all the arduous baggage of the real quest—dreams, visions, fasts, rituals, practices of extraordinary discipline, esoteric wisdom, transcendental experiences, and (especially important for us) magical songs—are no longer required. In their place, audiences get a MacGuffin. And as Hitchcock noted, it can be almost nothing.

So we shouldn’t be surprised to find the MacGuffin appearing at the dawn of the publishing business. When William Caxton set up the first printing press in England, he wasn’t seeking enlightenment, just profits. The old vision quest tradition linked to tales of King Arthur was unsuitable for that —at least in the form in which he inherited it—but he cannily understood it could be updated and modified in a way suitable for commerce. Today we would call it a brand franchise. Bill Caxton, in the year 1485 AD, is the first person in the English-speaking world to grasp its money-making potential. But the story had to be changed, and the object of the quest needed to be transformed into a physical object, and one which (as Hitchcock would later proclaim) was so vaguely described that almost nothing specific could be said about it. This original MacGuffin was the Holy Grail. In fact, all MacGuffins are a kind of Holy Grail. This is the strangest moment in the history of our culture. The quest was previously about transforming your life. Now it gets turned into a physical object—and a vague one, with all the key details missing. But before talking about this extraordinary object and its mysterious history, we need to acquaint ourselves with the Arthurian legend before it got turned into a commercial book, Le Morte d'Arthur, by publisher and bookseller Caxton. This will enable us to measure the huge gap between the traditional quest and the hero’s journey of the biggest brand franchises. At the very start of the Arthurian tradition, we encounter the peculiar notion that the singer is also a warrior hero. Scholars often admit puzzlement when confronted by these connections—for example when dealing with the surviving narrative of Uther Pendragon from The Book of Taliesin, where the father of King Arthur engages in a surprising monologue, conflating music and manslaughter. He starts by boasting about his valor in combat (“It is I who command in battle; I will not halt the conflict till blood’s been shed. . . . Arthur himself has no more than a ninth of my valor”), but soon switches to haughty claims about his preeminence as a musician (“I am a bard , and I’m also a harpist, I play on the pipe and also the crwth [lyre]. As great as that of seven score poets.” What a bizarre juxtaposition this is!—at least for modern-day scholars. Some claim that these are two different texts, squeezed together by mischance. They can’t comprehend a worldview in which songs and heroism are connected. But the continuity in meter, tone, and textual history refutes their skepticism. And this musician is not only a hero in battle, but is actually the begetter and parent of King Arthur himself—the key role model for today’s film franchises. The early bardic tradition is filled with these powerful musicians. Consider the most famous of all traditional Welsh story compilations, the Mabinogion, where we learn of Brân mounting an attack in a fierce war between the Welsh and Irish. We are told he “took all the string musicians on his back and made for Ireland.” Why do you need an army of musicians to mount a war? It’s ridiculous. . . . unless you live in a culture where musicians have special renown as participants or conductors or celebrants of heroic enterprises. The most significant figure in this tradition is Taliesin, a bard who lived in 6th century Wales and sang for at least three kings. The accumulated lore about this individual makes him seem more like myth than reality. For here we encounter every element of the traditional quest hero. Taliesin, as he is described in various texts is shaman, soothsayer, warrior, master of codes and altered mind states, traveler to the Otherworld (the Welsh Annwn), companion to King Arthur, and above all a singer who boasts of his superiority to all his peers. We are thousands of miles away from the Thracian origins of Orpheus, or the rituals of Native American dream seekers, or the shamanic communities of Siberia, yet here in Wales, the same playbook of the music-driven hero not only exists, but defines an entire cultural milieu. Of course, not everything we hear about Taliesin can be believed—but the main reason for this is that so many later bards adopted his name for their own work. This is always the pattern for the musical hero. The followers of Orpheus—the original model for the musician hero in the West—also pretended that they were Orpheus. Ficino was doing this as late as the Renaissance. Consider the power of this technique. You could be Orpheus, the exemplary musician who had mastered the byways of the Underworld. You could be Taliesin, the shaman warrior who foretold the future. You are now more than just a passive member of the audience—but are empowered to go on your own transformative musical journey. We find a similar imitation in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, where the deceased is sometimes described as “the Osiris.” In the best known version of this text, now located at the British Museum, the lowly scribe Ani adopts the persona of this grand Egyptian deity and ruler of the Underworld. If any confusion was involved, it was intentional—you wanted those you encountered on your journey to identify you with a formidable hero or deity. In this way, even a scribe (or a Certified Public Accountant, perhaps) could get a taste of the glory previously only allowed to elite warriors and powerful leaders. Such texts tell us of an expansive and inclusive perspective on heroism, markedly different from our stratified approach, one that sets the hero apart from the audience, who are merely invited to purchase a ticket and applaud at the end of the performance. This is precisely the significance of the music-driven tradition of heroes celebrated in this book. It’s an approach to a hero’s destiny that invites our emulation. We are expected to participate, provided we are willing to adopt the discipline and sacrifices involved, but with rewards for those who succeed—albeit ones that are often intangible and metaphysical, yet no less valuable for all of that.

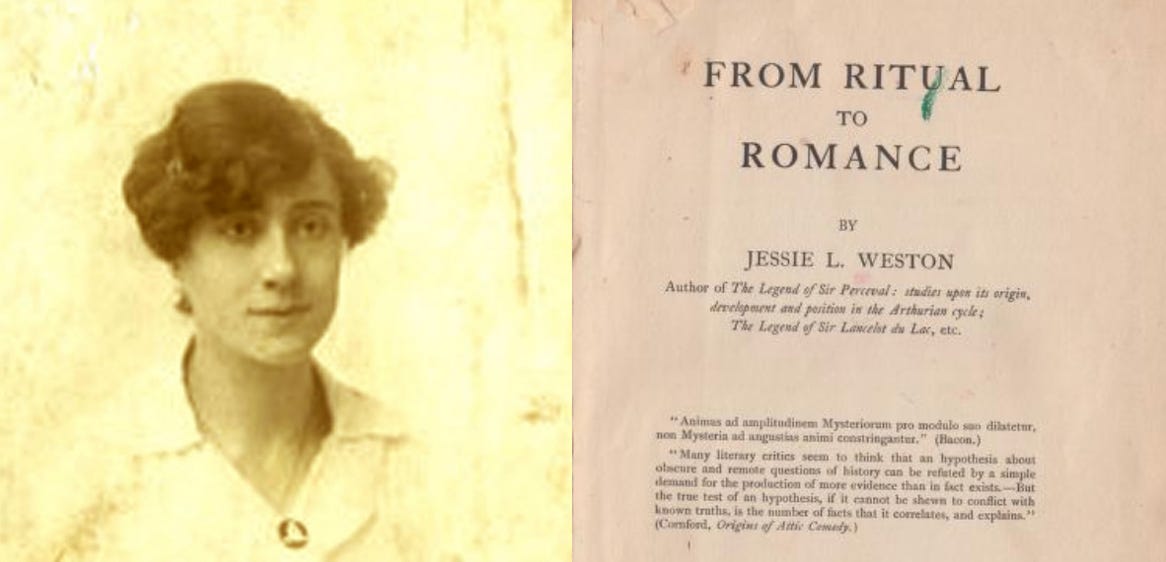

As late as the time of Chrétien de Troyes—five hundred years after the historical Taliesin—this kind of heroism still predominated in Western culture. Chrétien did more than anyone to turn the Arthurian legend into a literary phenomenon, leaving behind influential accounts of Lancelot, Percival, the Holy Grail, and other key elements that later storytellers would borrow and embellish. Some have even claimed that his work laid the foundation for the later rise of the novel. But Chrétien himself was a singer—he is the earliest known trouvère, playing a key role in bringing the song styles of the troubadours to the north of France. And his Arthurian tales are intensely rhythmic, with their rhyming eight-syllable couplets. In later years, heroic narratives would abandon these musical elements—perhaps unwisely, in my opinion—but at this stage (the twelfth century) the bardic tradition still defined the storyteller’s craft. Scholar Jessie L. Weston, who perhaps did more than anyone to connect these Arthurian stories of the hero’s journey with actual rituals and initiations, has argued that lurking behind the story of knights seeking the Holy Grail we find “abundant evidence that such a journey to the Worlds beyond was held to be an actual possibility —a venture to be undertaken by those who, greatly daring, felt that the attainment of such knowledge of the Future Life was worth all the risks.” Weston rightly points out that these accounts don’t just show up in imaginative literature, but permeate religious and historical documents as well. St. Paul initiated the tradition in Christianity by speaking of an amazing journey to the Third Heaven—noting that he met a person who had made the trip. But he wasn’t sure whether it happened in the traveler’s physical body or as an out-of-body experience. This kind of ambiguity is an essential part of the tradition—the real world and the alternative world are often contiguous or even overlap. So it’s never quite clear when you have left one and arrived at the other. We have encountered that already in the Native American vision quest tradition, and it’s also a key part of the Robert Johnson crossroads mythos where, as you recall, he allegedly made the leap into an alternate reality at an actual intersection of roads you could find on a map. A whole history of these dreamlike encounters is beyond the scope of this book, but once you are familiar with the broad outlines, you find them everywhere—from the medieval poem Owain Miles to the dream-influenced Enlightenment philosophy of Emanuel Swedenborg and all the way to modern times and peculiar individuals such as Edgar Cayce and Robert Monroe. Needless to say, musicologists pay no attention to these fringe figures—so the role of music in their stories is almost completely unexplored. Monroe’s memoirs, for example, may read like a Philip K. Dick sci-fi novel, but he funded extensive (and impressive) research into the role of sound patterns in these enhanced mental states, and his Hemi-Sync binaural beats technology is still used for a wide range of purposes—although I’ve never met a music scholar who has paid any serious attention to the work of the Monroe Institute. But the most interesting passages from Jessie L. Weston’s research into the hero’s journey are those in which she tells readers what she has omitted from her work. The first bizarre passage shows up in the introduction to her book From Ritual to Romance. Here she claims that “no inconsiderable part of the information at my disposal depended upon personal testimony, the testimony of those who knew of the continued existence of such a ritual, and had been actually initiated into its mysteries.” But then she refuses to share these firsthand accounts because scholars have “little respect” for these living rituals and prefer footnotes or extracts from manuscripts and books. This is an extraordinary admission. Weston is not only a 20th century figure, but is almost emblematic of the modernist mindset—T.S. Elliot took the title and much of the imagery of The Waste Land from her research. But she apparently had connections to cults that undertook ritualistic journeys to another world. We would love to know details, but nothing more appears until we are well into her book, and she adds a strange comment on Sir Gawain and the Grail legend. Here she reveals, via a passing remark hidden in a footnote, that the ancient cults she connects to the narrative “are not a dead but a living tradition (how truly living, the exclusively literary critic has little idea).” Again she drops the subject, only to raise it one final time. Once more the revelation is consigned to a footnote, this time near the very end of From Ritual to Romance. Here Weston claims: “Without entering into indiscreet details I may say that students of the Mysteries are well aware of the continued survival of this ritual under circumstances which correspond exactly with two of our Grail romances.” She never reveals sources or offers concrete details—if she were an initiate this may have been forbidden—but her claims are nonetheless extraordinary. She tells us that the hero’s journey to another world isn’t a myth or legend, but an ongoing practice in the modern world. That can’t be true. Or can it? Is there a secret organization of magical singers still operating in modern society, with roots going back to ancient pagan rituals? Is it possible that another pathway to heroism exists beyond sitting in a movie theater watching clichéd Hollywood films filled with MacGuffins? That seems so unlikely, maybe even impossible. Yet I’ve already shown how the mythos of blues musician Robert Johnson can only be understood in the context of the survival of this same tradition. And now we have evidence of another survival from across the Atlantic Ocean. But Jessie Weston would have no idea what would happen just one year after she published her book…. COMING SOON: Part Two of “What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in Pulp Fiction?” Notes: Welcome to the world of reality: David Foster Wallace, The Pale King (New York: Little, Brown, 2011), pp. 229-230. The main thing I’ve learned over the years: This and below from Peter Wuss, Cinematic Narration and its Psychological Impact: Functions of Cognition, Emotion and Play (Newcastle on Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2009) p. 176. It is I who command in battle: “Elegy for Uther Pendragon,” from The Book of Taliesin, translated by Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams (London: Penguin, 2019), pp. 111-112. took all the string musicians on his back: The Mabinogion translated by Jeffrey Gantz (London: Penguin, 1976), p. 75. abundant evidence that such a journey to the Worlds beyond: Jessie L. Weston, From Ritual to Romance (West Valley City, Utah, Walking Lion Press, 2007), p. 139. But the most interesting passages from Jessie L. Weston’s research: Ibid., p. 4. are not a dead but a living tradition: Ibid., p. 37. Without entering into indiscreet details: Ibid., p. 129. You're currently a free subscriber to The Honest Broker. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

What Is Really Inside the Briefcase in 'Pulp Fiction'?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Top 3 UX Design Articles of 2024 to Remember

Based on most subscriptions ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment