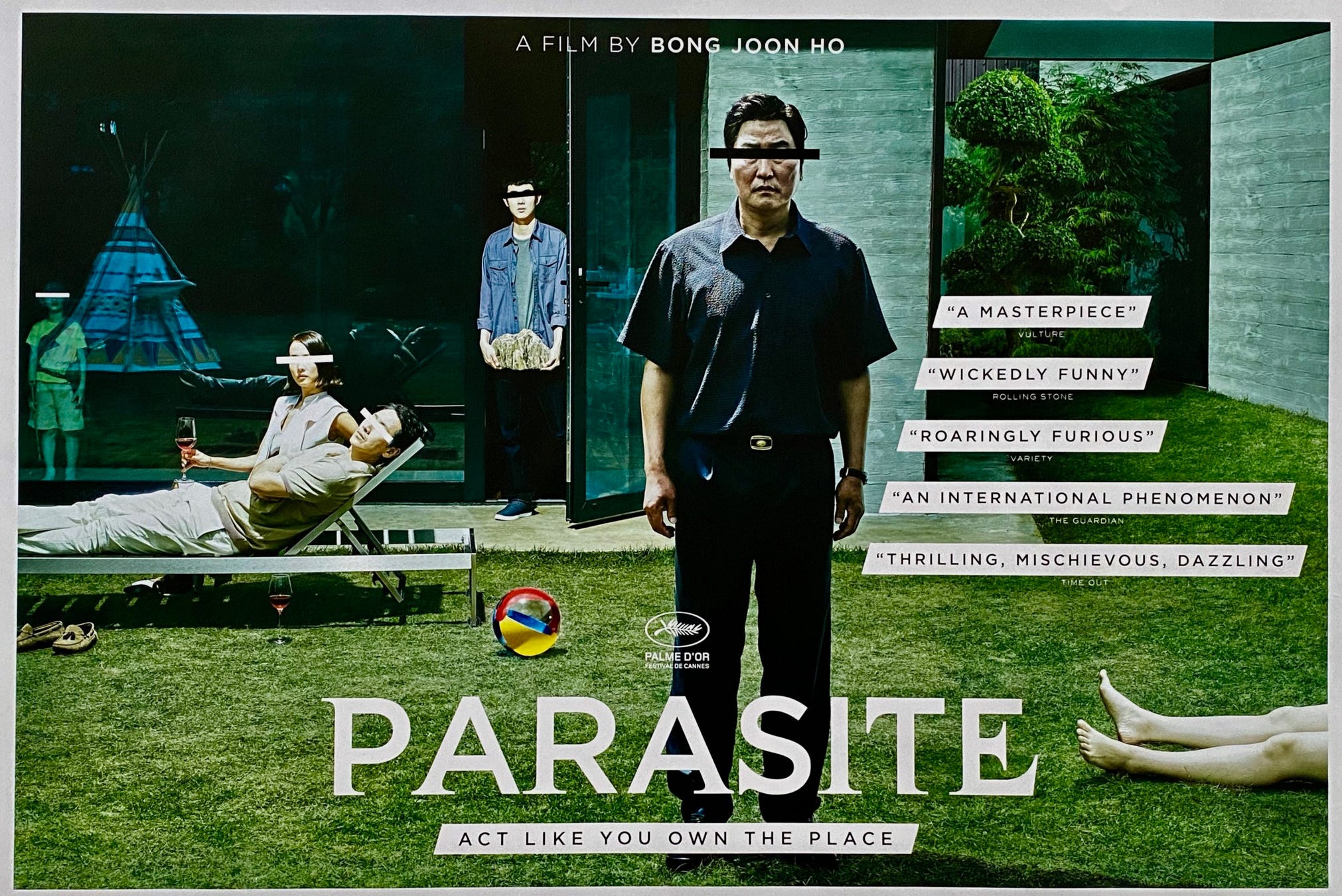

I don’t like thinking about parasites. My only personal experience occurred at the American Airlines terminal in LaGuardia a few years ago. I was seated at one of the tables, eating a Dunkin’ chocolate-frosted donut. And I noticed a bit of chocolate stuck to my finger. I tried wiping it off with a paper napkin. But the chocolate didn’t move. I tried again—but no luck. The chocolate was clearly stuck to my finger. That’s when I realized it wasn’t chocolate—it was a nasty tic sucking blood from my hand. Yes, this happened at the Food Court of LaGuardia Terminal B of all places! Somehow I’d become the meal myself. If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).How strange is that? I live in a countrified neighborhood where deer often graze on my front lawn (six of them simultaneously in the video below). But I don’t get a tic until I fly into New York. I did two things that day. First, I managed to extract the tic myself (not easy)—I stopped the bleeding and bandaged my finger. Second, I decided to fly into JFK instead of LaGuardia on all future New York trips. I’ve kept that vow. And I try to forget the incident—especially when eating donuts. But I’ve been thinking more about parasites recently. That’s because so many cultural institutions now resemble them. You might even say we live in a society where parasitical behavior is rewarded more than actual creativity. In the animal kingdom, 10% of known species are parasites. And for most of my lifetime, the same was probably true for the creative economy. We’ve always had parasites in the culture business. I’m referring to unsavory characters who make a living from plagiarism or piracy or some other scam. Maybe they sell bootleg records. Or peddle hacked Netflix passwords on the dark web. Or forge a Leonardo da Vinci painting. I’m not naive. I’ve shopped at street markets overseas where vendors peddle fake Nikes, fake Levis, fake Rolexes, fake everything.

Years ago when I did strategy consulting to Fortune 500 clients, we would sometimes devise parasite strategies (that’s exactly what we called them). But we did this simply as a thought exercise—we never actually presented these ideas to clients. Professional managers disliked these kinds of strategies back then (not anymore, as we shall see below). So we came up with these approaches simply as a way of grasping what others might do to us. Game theory (for example, the Prisoner’s Dilemma) will teach you many of these. But the basic rules of a parasite strategy are quite simple:

There are many examples in the real world. An extreme case is a dictator who lets a foreign company build a factory, and then seizes the assets. But if we had time, I could describe a wide range of parasite strategies, many of them quite legal. The key fact is that large professional businesses rarely engaged in these practices, until quite recently. They were the province of pirates and discounters and boiler room operators. And the parasites certainly didn’t live in billionaire mansions in Silicon Valley.

Nowadays, parasite businesses are the largest corporations in the world. Their technologies do many harmful things, but lately they have focused on serving up fake culture, leeching off the creativity of real human artists. Just take a look at the dominant digital platforms—and consider how little they actually create. But the amount of leeching they do is really quite stunning, especially when compared with the dominant businesses of the past.

Consider the case of the woman who attracted 713,000 TikTok followers and generated 11 million views for her videos—and got paid $1.85 over the course of five months. No that’s not $1.85 million—it’s one buck and eighty-five pennies. You can practically hear the lifeblood getting sucked out of the creator economy. Listen to the influencer below explain how he generated 60 million views on social media—and his payouts barely covered the cost of the phone he uses to upload his ‘content’.  I’m told that there’s a parasite that hovers around the eyes of cattle—it literally lives off blood, sweat, and tears (like some parody of Churchill). That’s a metaphor for much of the digital economy nowadays. Even well-paid influencers typically make money elsewhere—on branding deals, or merchandise, or spinoffs. That’s a lot easier than squeezing money from Meta.

Some platforms are more generous than others, but in every instance the parasite gets much richer than the creative talent. Hence, for the first time in history, the Forbes list of billionaires is filled with individuals who got rich via parasitical business strategies—creating almost nothing, but gorging themselves on the creativity of others. That’s how you get to the top in the digital age. Instead of US Steel, it’s Us steal. Instead of IBM, it’s IB Robbing U. But when parasites get too strong, they risk killing their hosts.

Recall that only ten percent of animal species are parasites. What happens if that number grows to 30% or 50% or 70%? That must have catastrophic consequences, no? This is precisely the situation in the digital culture right now. Google’s success in leeching off newspapers puts newspapers out of business. Musicians earn less and less, even as Spotify makes more and more. Hollywood is collapsing because it can’t compete with free video made by content providers. It’s no coincidence that these parasite platforms are the same companies investing heavily in AI. They must do this because even they understand that they are killing their hosts. When the host dies, AI-generated content can replace human creativity. Or—to be blunt about—the host will die because of AI-generated content. And then the web billionaires won’t even need to toss those few shekels at artists. It’s every parasite’s dream. The host can die, but the leech still lives on! But there’s one catch. Training AI requires the largest parasitical theft of intellectual property in history. Everything now gets seized and sucked dry. No pirate in history has pilfered with such ambition and audacity.

None of these companies offered this information voluntarily. The admissions came via court hearings, government investigations, leaked documents, and other indirect sources. Parasites like to operate stealthily. They don’t want you to notice. That’s even a telltale sign of a parasite business—it operates in the dark, without transparency. But this gets harder and harder as the parasite gets larger and larger. By comparison, that tic sucking my blood at LaGuardia was a small annoyance. The parasites in the culture are now too big enough to fit in an airplane hangar. Can we get rid of them? It won’t be easy. Once they’re attached, they don’t want to let go. But a good start would be:

These are all obvious steps—it’s really just common sense. Lawmakers could implement these immediately, and voters would overwhelmingly support these protections. The fact that this hasn’t happened already, suggests that our politicians just might be part of the parasite problem themselves. Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy The Honest Broker, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

Are We Now Living in a Parasite Culture?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Top 3 UX Design Articles of 2024 to Remember

Based on most subscriptions ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment