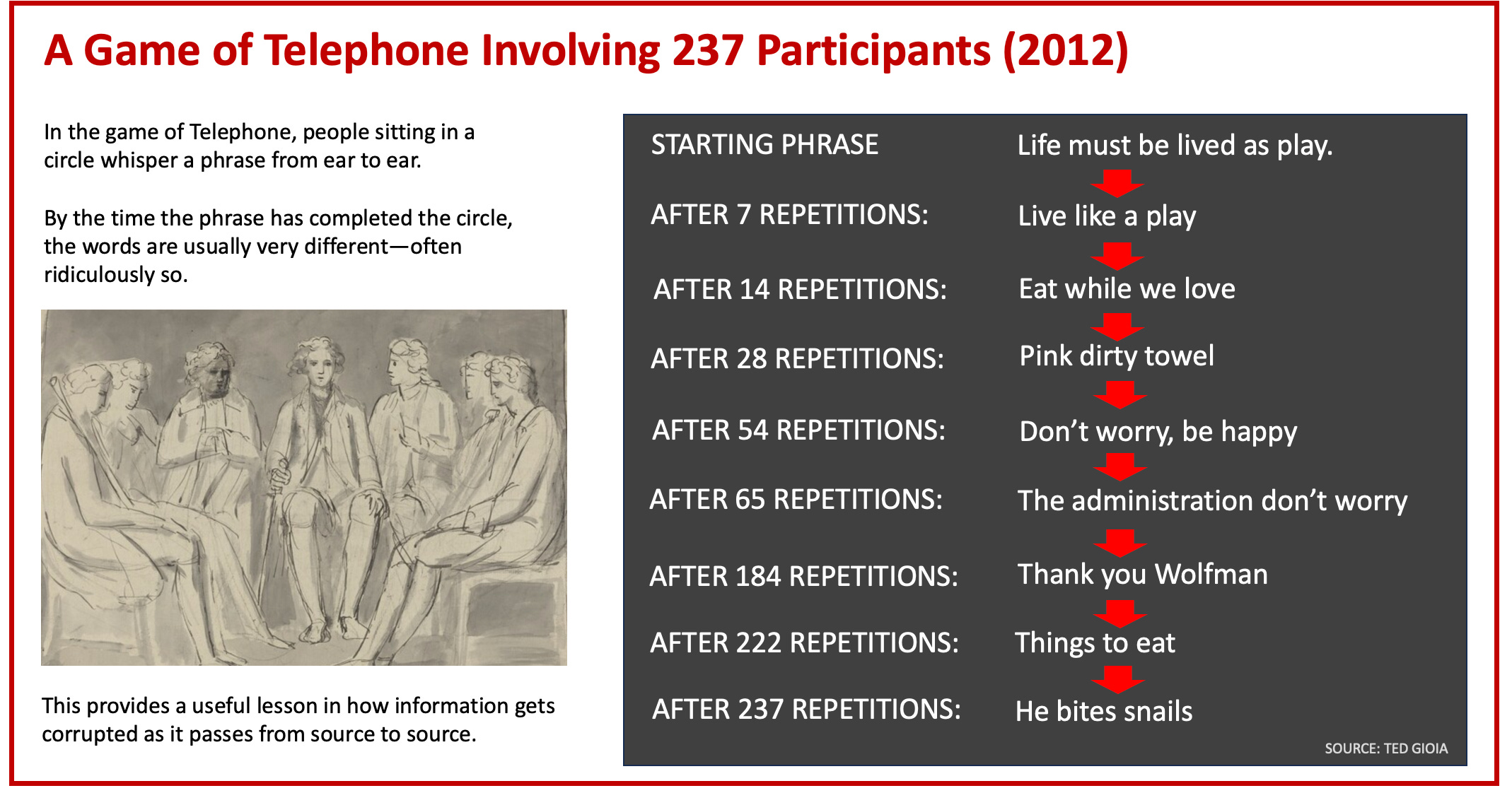

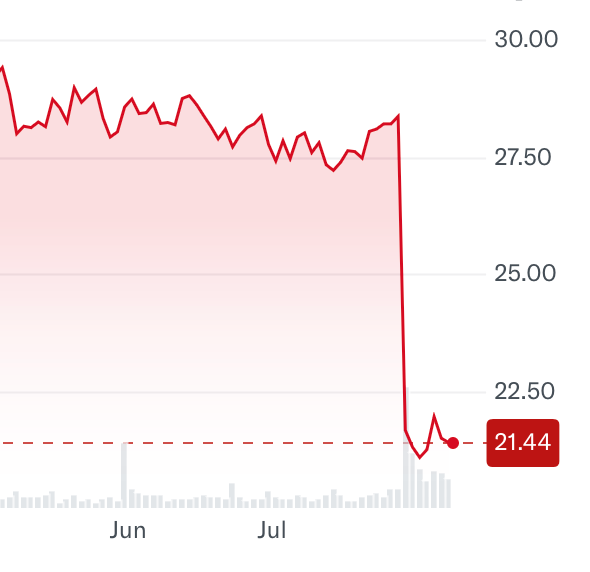

You might have played an old party game called Telephone—in which people sit in a circle, and whisper a simple phrase from ear to ear. By the time the information has moved around the entire circle, the words have changed. That’s because people mishear and misinterpret. So when a game of Telephone was played in 2012 with 237 individuals, the starting phrase was: “Life must be lived by play” (a quote from Plato). But when it reached the end of the circle, the words had turned into: “He bites snails.” Here’s how it progressed: In other instances, people have started with the phrase “Only the good die young” and end up with “The three Vikings visit Christ.” Or “Today the library is hot” somehow morphs into “Sharon Stone is my girlfriend.” Perhaps a degree of wish fulfillment enters into the game. Or as my mother used to say: “People hear what they want to hear.” If you want to support my work, take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).There’s a technical term for this process. It’s called generation loss. It has nothing to do with a lost generation—which is how Gertrude Stein described the Jazz Age. She famously told Ernest Hemingway: “You are all a lost generation.” I’m not talking about those kinds of generations. The generation loss we’re dealing with here refers to deteriorating data quality when a signal is repeated over and over again. Each time it’s generated, the information gets a little more corrupted. And it’s not just hearing that leads us astray. You can also measure generation loss if you make a photocopy of a photocopy. Each time you do it, the quality of the image gets worse. If you do it enough times, you can’t recognize what was in the original. Even digital data—which is supposedly copied and pasted with perfection—deteriorates with each repetition. Photos that are shared from account to account on Instagram get worse over time. In one experiment, a photo that was copied and reposted 90 times gradually turned into an unrecognizable blur.  The same degradation happens with music files and videos posted on YouTube. Going viral actually makes things worse. And now we have documented an extreme case of data collapse when AI is trained on AI inputs. In other words, generation loss is built into many of the key technologies of the digital age. The freshness of the original disappears, and is replaced by a degraded copy. Sometimes the decline happens so slowly, most people don’t even notice it. This problem is almost impossible to fix in a culture that relies heavily on algorithms. The algorithm is, by definition, a repeating pattern that always looks backward. It does something in the future based on what worked in the past. So the algorithm that recommends music or videos on a web platform will never deliver a totally fresh and new experience for you. It always gives you something similar to what you consumed last week—or last month, or last year. This is a simple example of a cultural doom loop. In this doom loop, anything exciting or fresh or different is punished—or sometimes eliminated completely. You aren’t even allowed to consider it as an option. That’s how the system is built. And here’s the irony—a technology that promises progress actually creates regress. It gives you stale bread when you want a fresh loaf. In a cultural doom loop, newness is too risky. It’s too unproven. It can’t be relied on. So you must be protected from it. But sometimes the riskiest way to live is avoiding all risk. I’ve seen this over and over again. I learned early in my career at the Boston Consulting Group that many companies fail by taking the safest path. The first time I saw this, I thought it was some paradox or anomaly. How can you destroy yourself by maximizing safety? But it happens. In fact, It happens all the time in business. This was actually the single most frequent strategic mistake made by big corporations. I could write a whole book on that—how business empires collapse through safe, risk-free decisions. This is why Hollywood is in a state of crisis right now. They thought the safest strategy was to release proven brand franchise films. But the franchises start to suffer from generation loss—and audiences can smell the rot. The same thing is happening in music. That’s is why Universal Music’s stock price collapsed recently. Even though revenues were up, shareholders could see that the this backward-looking business model is actually quite risky.

Here, too, the bosses believe that owning familiar hits is the safest possible strategy. But they are wrong. The participants may not see that yet, but they will eventually—because investors already do. You can’t build the future if you’re living in yesterday. That’s how Sears collapsed. That’s how Xerox collapsed. That’s how Kodak collapsed. That’s how Blockbuster collapsed. And I could give a hundred more examples. And, of course, this also happens in the lives of individuals. Therapists get rich from patients who keep repeating patterns from the past that have stopped working—or, in some cases, never worked. And, yes, this also happens in entire societies. These are the most extreme examples of cultural doom loops.

There are plenty of examples of this in human history. After the collapse of Rome, many leading medieval thinkers tried to hold on to the wisdom of the past. Some very dedicated and disciplined individuals devoted their entire lives to this process—their job title actually was copyist. That pretty much says it all. These people copied down the same manuscripts over and over again—it’s not even clear that they always understood what they were copying. I’m sure many of them would have killed for a Xerox 9200.  We’re grateful for their efforts today, but only because later generations (in the Renaissance, for example) recognized that bold people could build something new from these old foundations. Unlike today’s movie and music moguls—who also deserve to be called copyists—they eventually learned that you can’t milk old IP forever. Share the fun—give a gift subscription to The Honest Broker.You can find many cultural doom loops in stagnant societies. These occur when reverence for the past (or the ancestors or traditional ways or dogma) becomes so extreme that cultural practices suffer from generation loss. I believe this helps us answer many puzzling questions about the history of technology. Scholars have sometimes asked why the Industrial Revolution didn’t happen in ancient Rome or China or the medieval Arabic world—all of which had advanced conceptual knowledge and significant construction and engineering skills. But each of these societies was, in some degree, a victim of their own past successes. At a certain point, their respect for the past began to constrain their boldness in addressing the future. We do well to learn from these situations. In some ways, the more advanced societies are the most vulnerable—because they have the greatest tendency to repeat patterns from a triumphant past. The addition of digital technology has only changed one thing in this dynamic. The process of generation loss happens much more rapidly. What should we expect when a doom loop accelerates (as is occurring now in so many contexts)? Maybe—if we’re lucky—it comes to an end faster, without a long dynastic period of stagnancy. That may seem like too much to hope for. The people creating today’s doom loops are, for the most part, stubborn and narcissistic and very, very powerful. They don’t like admitting they’ve made mistakes. Those folks might really be a lost generation—I’m pretty sure Gertrude Stein would agree. After all, she was skeptical of NorCal long before Silicon Valley shipped its first chip. Can we really expect the doom loopers themselves to change direction? Frankly, they might not have a choice. They are spending huge Godzilla-sized amounts of money on building these doom loops, and those cash sources dry up quickly if results fall short of the over-hyped expectations. Many of the protagonists in this story have already crashed and burned in recent months. And you should expect more of the same in the immediate future. In other words, the ground is already starting to shift. Something is coming to a head in our society. I can feel it in the air—maybe you can too. Many of the predictions I’ve made about this have already come true (see, for example, here and here and here and here and here). But we haven’t even reached halftime in this contest yet. I think some of us can already start to guess the winners and losers. But we still need to hold on tight—because this ride could get very bumpy before it ends. Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy The Honest Broker, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

How to Know If You're Living in a Doom Loop

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

When Bad People Make Good Art

I offer six guidelines on cancel culture ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment