👋 Hey, I’m Lenny and welcome to a 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒 of my weekly newsletter. Each week I tackle reader questions about building product, driving growth, and accelerating your career.

It’ll take 3 minutes and will impact the future of my newsletter and podcast 👇

Start survey

Q: How do I know if I should pivot or stay the course?

In part one, I shared the largest-ever data set of startup pivots. The Google Sheet within the post (available to paid subscribers) includes the stories behind 40 pivots—why they decided to pivot, how they found their new idea, how long it took them to decide, and more. Today, I’m going to analyze this data and share the many lessons that emerged.

It’s heartbreaking to pivot. You are thinking about killing an idea you’ve been obsessed with for months or years. Your team joined because of it, you’ve built a lot of great product around it (so much sunk cost!), and some people probably love what you’ve done. You’ve spent so long convincing people (and yourself) that this is a huge idea. And who knows—if you give it just a bit more time, it could still work!

No single post, video, or tweet is going to give you a definitive answer for whether you should pivot or not, but the truth is that pulling the plug on one thing often allows something much better to flow through.

As Dalton Caldwell (Managing Director at Y Combinator), in his legendary talk on pivoting points out, pivoting is all about opportunity cost:

“[Pivoting] gets more shots on goal to try to find this elusive thing [called product-market fit]. If you made something and you launched it and it’s like, ‘Meh, not really working,’ a dang good reason to pivot is you get another roll of the dice. I’ve seen people use these opportunities really well. It’s much easier to be lucky when you get half a dozen shots on goal than one.”

As I was doing this research, I realized that people mix up two very different types of pivots and that it’s important to differentiate which path you’re on:

Ideation pivots: This is when an early-stage startup changes its idea before having a fully formed product or meaningful traction. These pivots are easy to make, normally happen quickly after launch, and the new idea is often completely unrelated to the previous one. For example, Brex went from VR headsets to business banking, Retool went from Venmo for the U.K. to a no-code internal tools app, and Okta went from reliability monitoring to identity management all in under three months. YouTube changed direction from a dating site to a video streaming platform in less than a week.

Hard pivots: This is when a company with a live product and real users/customers changes direction. In these cases, you are truly “pivoting”—keeping one element of the previous idea and doubling down on it. For example, Instagram stripped down its check-in app and went all in on its photo-sharing feature, Slack on its internal chat tool, and Loom on its screen recording feature.

Occasionally a pivot is a mix of the two (i.e. you’re pivoting multiple times over 1+ years), but generally, when you’re following the advice below, make sure you’re clear on which category you’re in.

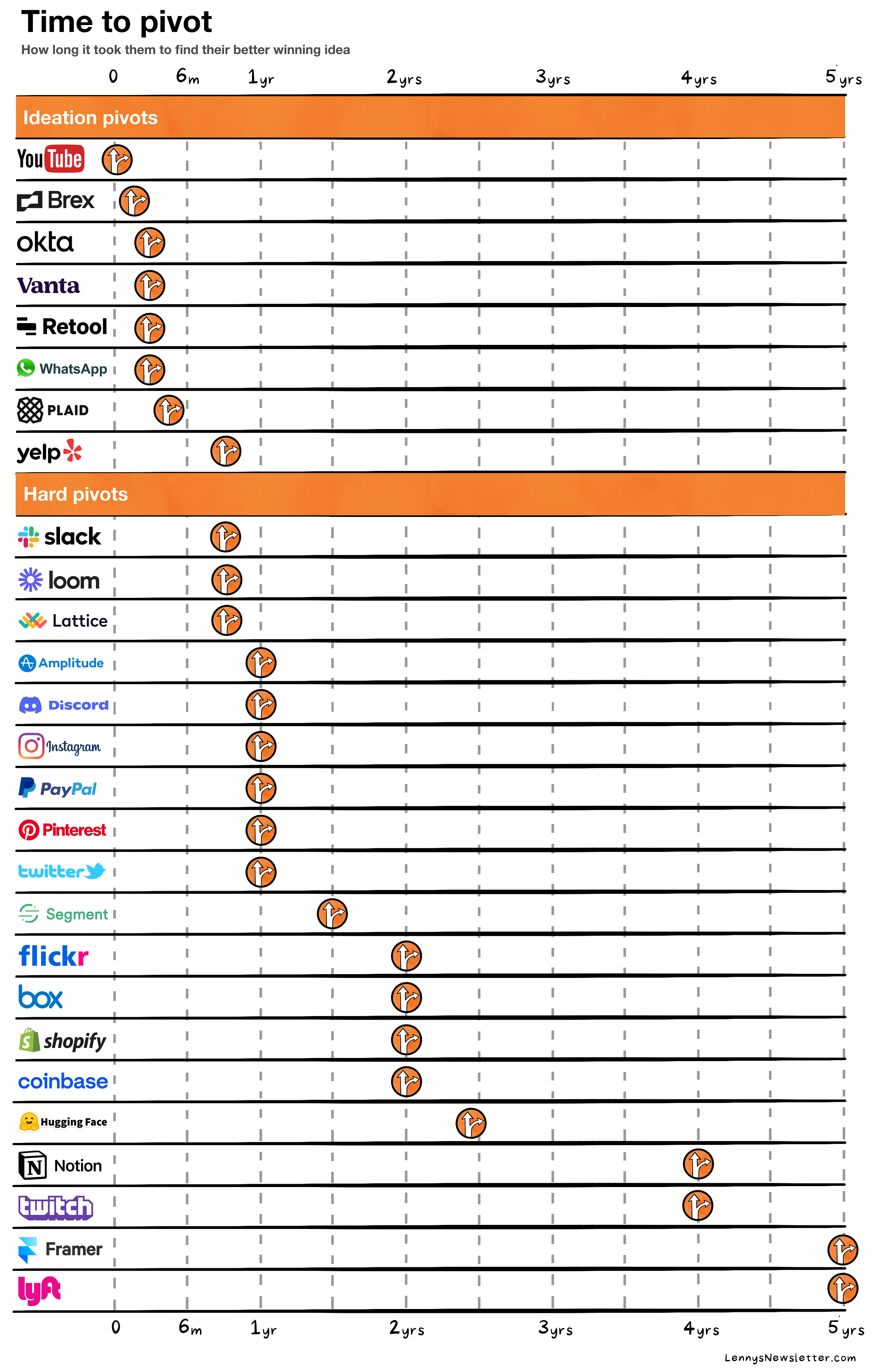

When looking at the data, a few interesting trends emerged:

Ideation pivots generally happen within three months of launching your original idea. Note, a launch at this stage is typically just telling a bunch of your friends and colleagues about it.

Hard pivots generally happen within two years after launch, and most around the one-year mark. I suspect the small number of companies that took longer regret not changing course earlier.

My takeaway is that you should have a hard conversation with your co-founder around the three-month mark, and depending on how it’s going (see below), either re-commit or change the idea. Then schedule a yearly check-in. If things are clicking, full speed ahead. If things feel meh, at least spend a few days talking about other potential directions.

Remember, you’re probably waiting too long to pivot. If you’ve tried your best ideas and they aren’t clicking, it’s unlikely that a few additional features will all of a sudden change everything. See: The next feature fallacy.

Reasons to strongly consider a pivot are very clear across both the data and the advice from folks who’ve seen a lot of pivots:

Persistent lukewarm interest

Realizing it’s never going to be as big as you thought

Here are examples of each.

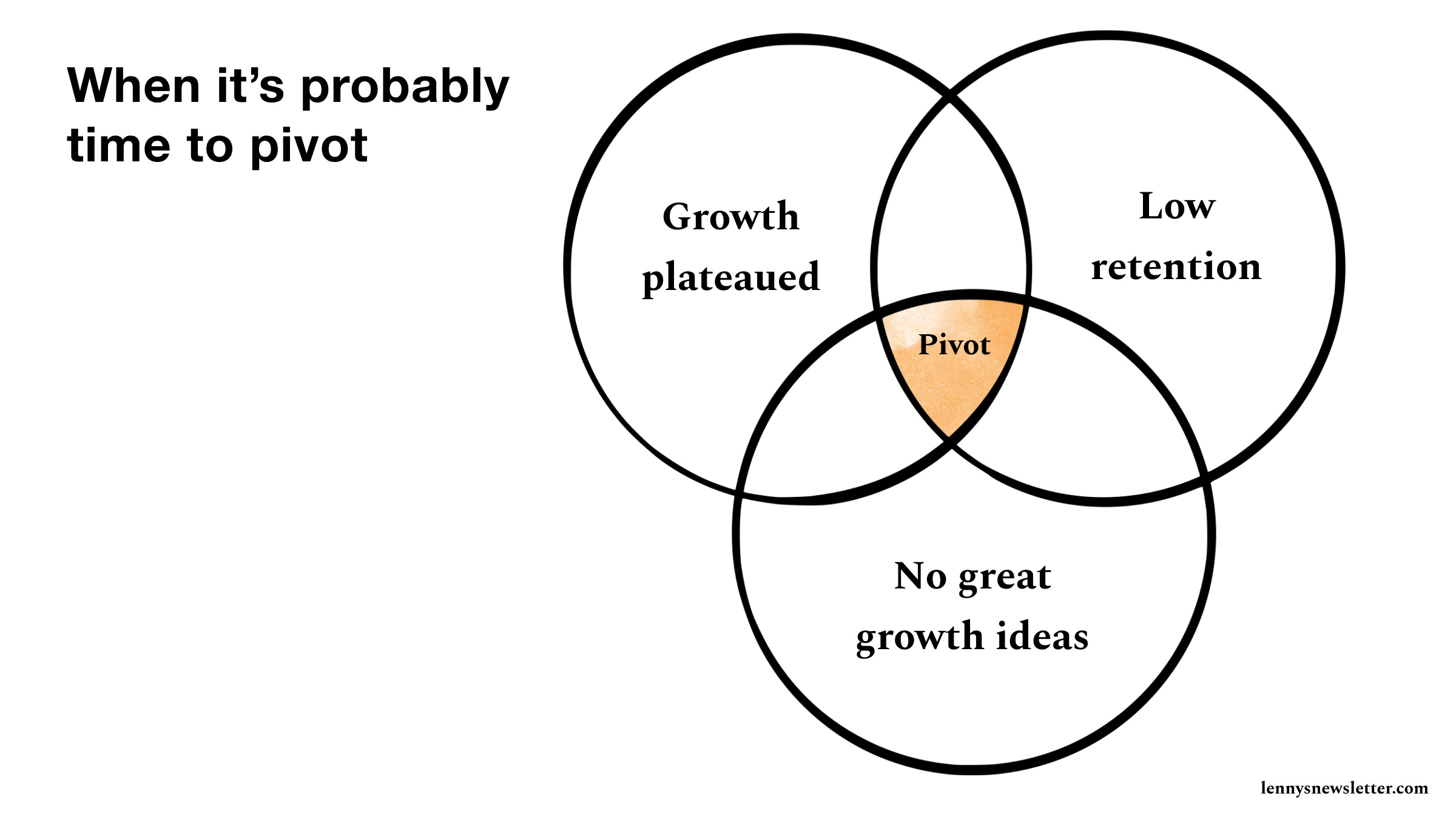

If you see very low retention, a consistent growth plateau, and largely lukewarm interest in your idea, and you don’t have any more good ideas to drive growth, it’s probably time to pivot. It’s hard to put a super-strict time frame on this, but I’d say give it two to three months during the ideation phase, and six or more months if you have a live product with meaningful traction. But be sure to read this whole post before making the decision, since there are also good reasons to keep going.

To make this more real, here’s what it felt like to founders right before they pivoted:

Instagram:

“We knew it wasn’t working when we would give it to people and they’d just keep bouncing off.”

—Kevin Systrom, CEO and co-founder

Amplitude:

“Sonalight did decently well, reaching hundreds of thousands of downloads and some number of paying customers, but it never really became a mainstream success. Our retention was very poor because the accuracy of the voice recognition wasn’t good enough yet.”

—Spenser Skates, co-founder and CEO

Twitch:

“We started trying to reignite growth and we had all these ideas for products we’d build, but they pretty much all failed in a variety of different ways. We were bumbling around, and a VC came by and told us, you’re doomed. Reigniting growth is almost impossible once it stops. And if you’re not growing on the internet, you’re dying.”

—Emmett Shear, co-founder, via “How I Built This”

Notion:

“A lot of the early stuff didn’t stick. The retention was not great, and it was very buggy.”

—Akshay Kothari, co-founder and COO

Segment:

“Counting laptop screens, it’d be looking over the shoulders of the students, and we discovered at the beginning of class about 60% of students were on Facebook [not using our product] and by the end about 80% were on Facebook.”

—Peter Reinhardt, co-founder and CEO

Lattice:

“We would have pivoted more quickly, but it appeared to be at least sort of working; we got a good amount of top-of-funnel interest (in fact, OKRs are still a major reason people come to look at Lattice) and some great customers who signed up. However, the user retention was really bad, and after a few months there was a massive drop-off in how many employees were using the tool. So eventually we just recognized that this would never be the foundation for a growing business and knew we needed to pivot.”

—Jack Altman, CEO and co-founder

Yelp:

“When we launched Yelp, in my heart of hearts I tried to remind myself, as painful as it was, that we probably didn’t get it perfectly right. Even though we thought we were super-geniuses, there’s probably some way that we got it wildly wrong and we should look for something that is working, if it doesn’t work. So as soon as we launched, that’s what I was doing. Especially as the data that’s coming in, it’s like … people don’t like the site very much.”

—Jeremy Stoppelman, CEO and co-founder

Loom:

“Seven months in, we only made $600.”

—Shahed Khan, co-founder

For many founders, it wasn’t so much seeing hard data as it was just realizing they were mistaken about the potential of the idea. With time and the additional experience of building the thing, it’s not at all surprising that you may realize your idea is simply not good enough.

Brex:

“We applied to YC with this VR idea, which, looking back, it was pretty bad, but at the time we thought it was great. And within YC, we were like, ‘Yeah, we don’t even know where to start to build this.’”

—Henrique Dubugras, co-founder and CEO

Slack:

“We came to the conclusion that Glitch was never going to be the kind of business that would have justified the $17.2 million in venture capital investment [that we raised]. It might have been a neat project for a half-dozen people if we had spent a million dollars to get there, but by the end of 2012, there were 45 people working on it, we had spent many millions of dollars, and it just wasn’t ever going to scale. So we decided to shut it down without knowing what we were going to do next.”

—Stewart Butterfield, founder and former CEO, via Business Insider

YouTube:

“The whole thing didn’t make any sense. We were so desperate for some actual dating videos, whatever that even means, that we turned into the website any desperate person would turn to—Craigslist.’ Despite offering to pay women $20 to upload videos of themselves to YouTube, nobody came forward, forcing Chen, Karim and co-founder Chad Hurley to adopt a different strategy.”

—Steve Chen, co-founder, via The Guardian

Box:

“We looked at our user base and said, 2% to 3% of people are paying. And we did the math on how long it would take us to build a real business here when you have 2% to 3% of people paying.

We got to this struggle: you either had to be a consumer product that really optimized for consumer products, like upsell percentage, consumer use cases, all of that. Or we were listening to customers and heard more advanced and significant business use cases, like better security, business processes, and sharing files across enterprise. That was an entirely different segment of the market but with the same foundation of ‘make it really easy to share files and power how businesses work.’ So we said, OK, we think this is a bigger opportunity in the business space.”

—Aaron Levie, co-founder and CEO

Discord:

“We soft-launched Fates Forever in the fall of 2013 and, after months of testing, had a hunch it wasn’t going to be a hit, but we released it anyway in the spring of 2014 to confirm. At that point it was pretty clear it wasn’t working as is (an iPad MOBA), but we committed to post-content updates for a bit while starting to port it to iPhone and explore other ideas. I think it was winter 2014 when we first started seriously discussing the Discord concept.”

—Jason Citron, co-founder and CEO

Flickr:

“We were never going to raise money for the game. I had tried everything. I had put all of my savings into it, we had tapped out friends and family. We had more or less worked through all of the very small amount of angel investment we were able to get.”

—Stewart Butterfield, CEO and co-founder, via “Masters of Scale”

No comments:

Post a Comment