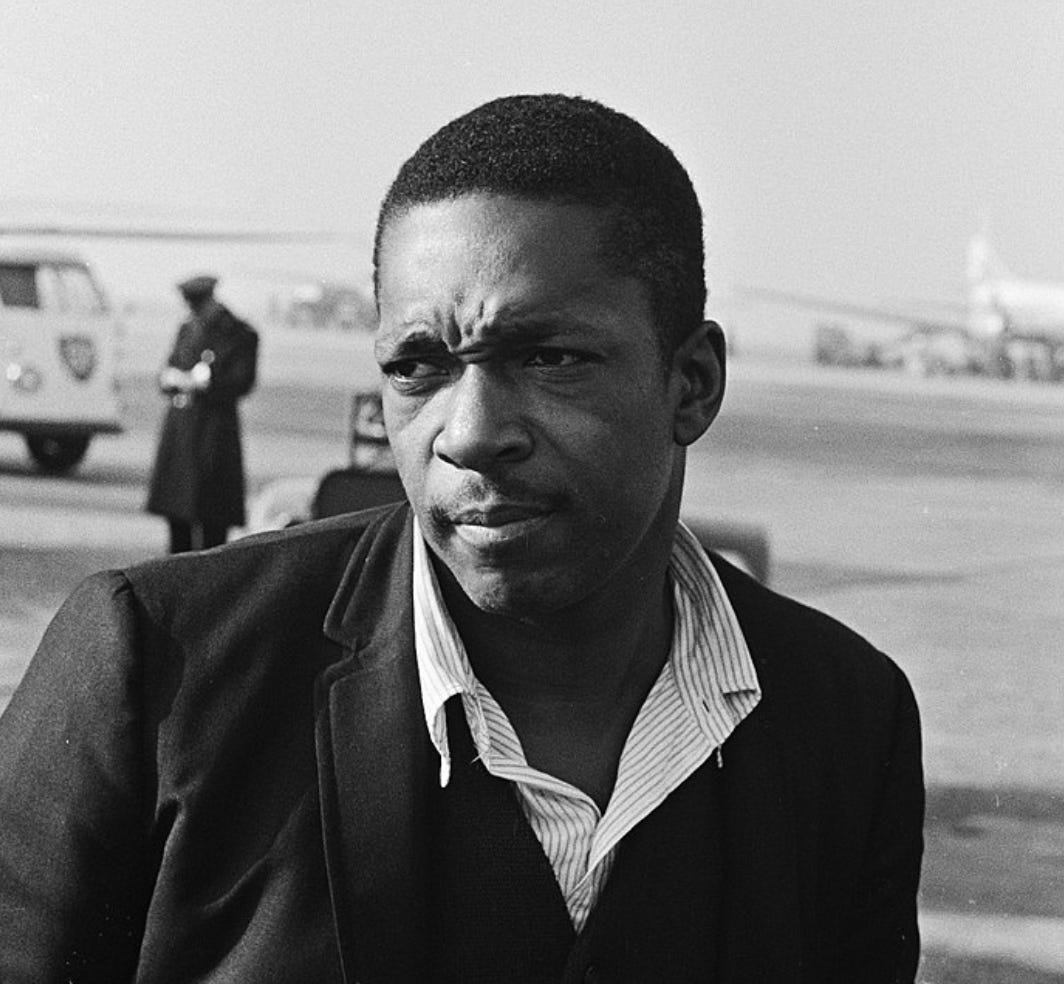

How Miles Davis Hired John ColtraneA fascinating interlude from James Kaplan's new book '3 Shades of Blue'I’m sharing below a section from James Kaplan’s outstanding new book 3 Shades of Blue. Kaplan focuses on three artists who had a transformative impact on jazz: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Bill Evans. The stature of these artists is sufficient reason to pay attention to this well-researched work. But Kaplan is especially skilled as a storyteller, and has delivered the most readable narrative account to date of a milestone moment in American music. Below he tells how Miles Davis hired John Coltrane. The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.Why he picked me I don’t knowBy James Kaplan From 3 Shades of Blue: Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Bill Evans, and the Lost Empire of Cool (Penguin 2024)After Johnny Hodges fired him, John Coltrane was back in Philadelphia and spottily employed—so spottily that he was without a job for New Year’s Eve of 1954. And so, out of pity, and in gratitude for some musical pointers Coltrane had given him, a trumpeter friend named Ted Curson took him along to a gig in Vineland, New Jersey. Curson, who went on to have a solid jazz career, remembered the evening decades later. “He played ‘Nancy with the Laughing Face,’ I’ll never forget that,” he said. “I never heard anything so great, so intense, with so much feeling.” Along with all his other musical strengths, Coltrane had a beautiful way with ballads. But his work problems had nothing to do with musical skill. He was a heroin addict, with the same set of handicaps that had crippled Miles Davis’s career from 1949 to 1954: unreliability and general dishevelment made steady work next to impossible. Leading a working band was out of the question. So he picked up whatever gigs he could, when he could. One now-and-then job in 1955 was as part of an ad hoc trio called the Hi-Tones, with the great jazz organist Shirley Scott and the youngest Heath brother, Albert (“Tootie”), on drums. All three were dead-serious, technically sophisticated players. “We were too musical for certain rooms,” Coltrane recalled. “Coltrane was phenomenal even then,” Scott said. “We played in and around Philadelphia on and off for at least a year….We played bebop (including ‘Half Nelson’ and ‘Groovin’ High’), straight-ahead music….We did rehearse a lot, and we had a lot of arrangements, most of them John’s.” Then came the call from Philly Joe Jones. Philly Joe—Joseph Rudolph Jones had taken on the nickname to differentiate himself from the great swing drummer Jo Jones—went way back with Coltrane: the two had started gigging around town with Percy Heath soon after Coltrane’s discharge from the navy. Three years older than the saxophonist, Jones was as different from the quiet, serious, monomaniacal Trane as different could be: he was a brilliant, highly articulate extrovert, a skilled tap dancer and mimic. He was also a serious heroin addict. “Philly Joe Jones was the Babe Ruth of junkies,” one longtime observer of jazz told me. “I mean, he was the junkie. He was the cat.” Jones and Miles also went back: for a while during Davis’s dark years, the two had barnstormed around the Midwest together, Philly Joe going ahead of Miles to pick up local sidemen in each city. The results were consistently disappointing. Still, it had fed them for a while—fed the monkey on their backs, too. Miles never made a secret of the fact that Philly Joe was his favorite drummer. “He knew everything I was going to do, everything I was going to play,” Davis said; “he anticipated me, felt what I was thinking.” Jones had a special rim shot that he liked to hit immediately after a Miles solo: it became known around jazz as a Philly lick. Soon, other musicians began asking their drummers for it, too. “I left a lot of space in the music for Philly to fill up,” Miles said. “Philly Joe was the kind of drummer that I knew my music had to have. (Even after he left I would listen for a little of Philly Joe in all the drummers I had later.)” Miles had tapped Jones to contact Coltrane much as he’d deputized the drummer to find sidemen back in the day, only in this case the need was more urgent: Jack Whittemore had set up a tour for the Miles Davis Quintet— Baltimore, Detroit, then back to New York at Birdland and Café Bohemia—but with Sonny Rollins and now John Gilmore out of the picture, the quintet was a quartet. Coltrane was working at Spider Kelly’s in Philadelphia with the organist Jimmy Smith when Philly Joe called and asked if he could come rehearse with the band. Recognizing that this could be his shot at the big time, Trane asked Smith for a few days off and went to New York, where things did not go well. John Coltrane would ultimately become a jazz deity, by virtue of his supreme technical skills, his ceaseless exploration of the far bounds of the music, and the intense spirituality that informed his life and art. But in 1955 he was an awkward outsider, as far as possible from any kind of distinction in his field. (Even his heroin addiction—desperate, furtive, ashamed—didn’t fit into the cool model of jazz culture.) In auditioning for Miles he was virtually coming out from hiding, having spent the past decade freelancing around jazz’s seamy outskirts as he searched musically; yet even as his playing improved, he gained little faith in his own abilities. His ceaseless questing for musical and spiritual enlightenment filled him with questions about everything, especially music. And in reencountering a newly ascendant Miles Davis, he was coming up against the ultimate non-answerer. “Miles is sort of a strange guy,” he would tell François Postif in 1961. “He doesn’t talk a lot, and he rarely discusses music. You always have the impression that he’s in a bad mood, and that he’s not interested in or affected by what other people are doing. It’s very hard, in a situation like that, to know exactly what you should do….”

Two good things quickly became apparent in those September tryouts: that Coltrane’s abilities as a player had advanced considerably since that long-ago gig at the Audubon Ballroom, and that he knew Miles’s repertoire. What was less good, Davis recalled many years later, was that “Trane like to ask all these motherfucking questions…about what he should or shouldn’t play. Man, fuck that shit; to me he was a professional musician and I have always wanted whoever played with me to find their own place in the music. So my silence and evil looks probably turned him off.” It was an odd business, this angry aloofness of Miles: on the one hand it seems to have been kind of worked up, put on like a vestment of fame and entitlement; on the other hand, at first he and Coltrane seem to have genuinely rubbed each other the wrong way. After a couple of days of rehearsing, the saxophonist told Davis he had to go back to Philadelphia, and left. If he had secretly wanted Miles to cut out the unpleasant behavior and hire him, Coltrane couldn’t have come up with a better strategy than walking away. The first date on the tour, at Baltimore’s Club Las Vegas, was rapidly approaching, and Davis still had a hole in the lineup. Coltrane could play, and he knew all the tunes: “We practically had to beg him to join the band,” Miles recalled. Coltrane joined. For more information on 3 Shades of Blue, click here. You're currently a free subscriber to The Honest Broker. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

How Miles Davis Hired John Coltrane

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

When Bad People Make Good Art

I offer six guidelines on cancel culture ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment