The Pulse: Will US companies hire fewer engineers due to Section 174?It’s rare that a tax change causes panic across the tech industry, but it’s happening in the US. If Section 174 tax changes stay, the US will be one of the least desirable countries to launch startups👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a bonus, free issue of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover topics related to Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. In this article, we cover one out of four topics from today’s subscriber-only The Pulse issue. To get full issues twice a week, subscribe here. In October, we looked into bootstrapped companies founded by software engineers and the article resonated with many readers; I got lots of messages from bootstrapped founders following that issue. Many messages were complaints about something called “Section 174 changes.” Here’s what one founder said:

I did some research, and The Wall Street Journal and a handful of other news outlets have covered this change since last March. Still, founders reaching out shared that it feels like public awareness is low about just how large a problem this tax change is. I took to social media to gather more information, and a surprising number of complaints from US tech businesses came in. In this issue, we cover:

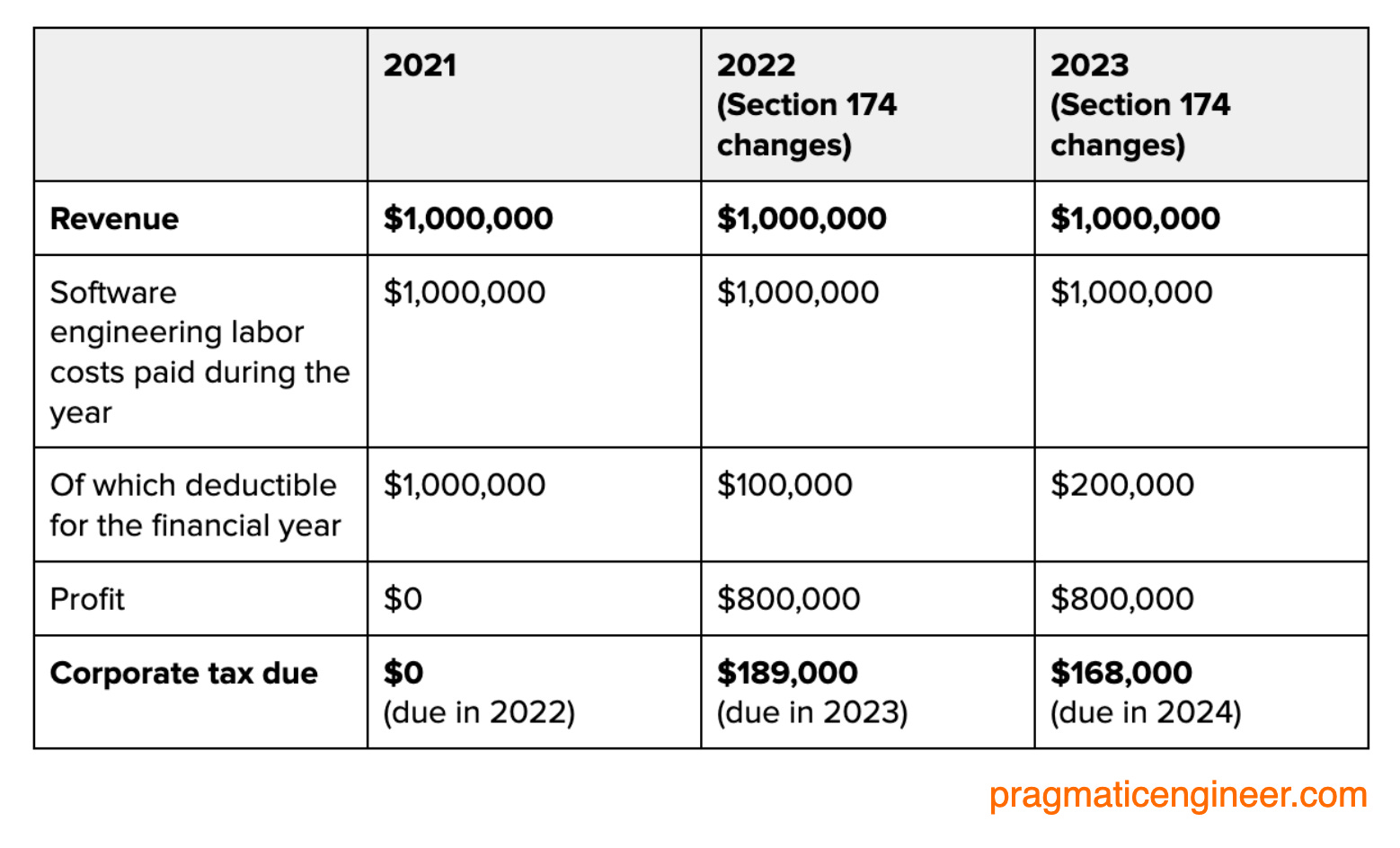

An unexpectedly high tax bill out of nowhereMany US software businesses amassed surprisingly high tax bills in 2023, seemingly out of nowhere, due to a tax change which took effect in July the previous year, which many small companies knew nothing about until finalizing their 2022 returns. The change was expected to be repealed (reversed) in December 2022, so many accountants didn’t inform customers for that reason. So, businesses got a surprise when the first tax payments fell due last April. The amendment to S174 means employing software engineers can no longer be accounted as a direct cost in the year they are paid – unlike the norm, globally. Here’s a simplified example of the change from the final tax year before the change. Take an imaginary bootstrapped software business called “Acme Corp.” This company generates $1,000,000 of revenue per year running a SaaS service. It employs five engineers, and pays each $200,000. That is $1,000,000 paid in labor costs. For simplicity, we omit other costs like servers and hosting, even though those costs can also fall under the new R&D rules, and have to be amortized. So, how much taxable profit does this company make? In 2021, the answer would be zero profit. In 2022, the answer was $900,000 in profits(!!) This is because from 2022, software engineer labor costs must be amortized over five years. Here is how amortization works:

Let’s break this down: What happens to a small, bootstrapped company without $189,000 in cash floating around with which to pay this tax? There are two options:

Less hiring of software engineers and more software engineering layoffs are already happening at smaller US tech companies. In January last year, in a Wall Street Journal article, policy analyst, Alex Muresianu, estimated this tax code change would cost the US about 20,000 full-time software engineering jobs. And I have more real-world accounts of how US businesses are being hit, straight from the companies themselves:

A tax change never intended to make it into lawSo, what is “Section 174?” We need to go back some years to understand. In 2017, then-President, Donald Trump, signed the 2017 Tax Cuts & Jobs act, which overhauled tax codes and reduced tax – for example, it reduced the top tax bracket from 39.6% to 37%. To make the bill pass strict budgetary rules, the Senate used a process called reconciliation: adding in tax code changes that delayed tax increases. These delayed increases “balanced out” the tax reduction. One of these changes was Section 174, set to come into effect 5 years later, in 2022. These parts deliver the blow by making it clear that software development costs need to be amortized over 5-15 years. Most experts expected Congress to push back the Section 174 amendment to a later date, or simply remove it. But Congressional negotiations to repeal the changes fell apart at the last minute in December 2022, meaning it became law. Why did Big Tech or VCs not raise the alarm?Why did we not hear the largest tech companies protesting the tax change? Actually, several did, but their protests failed to cut through on the news agenda. Large tech companies tend to speak up about issues like this via coalitions, trade associations, and lobbyists. Amazon, Microsoft, Intel, Ford, Lockheed Martin, and other US companies created the US R&D Coalition in 2018 to advocate in reversing this change. This group concludes:

Here is how the S174 change impacted some companies, based on what I found in their annual reports:

For companies with large cash reserves, the tax change was inconvenient, but manageable. Over a five-year period, the amount of tax evens out. After five years, there can even be tax benefits to this kind of accounting. What about VC-funded companies? For loss-making companies this change doesn’t make much of a difference. But the change does impact VC-funded companies near to break even. Most VC-funded companies close to breakeven have big-enough cash buffers with which to pay unexpected tax bills. However, these companies might reduce hiring – or even consider letting go staff. Impact on US tech companies and devs working at themAssuming Section 174 stays and all US companies must amortize software developer costs over 5 years, this will have an immediate impact on early-stage and small tech companies:

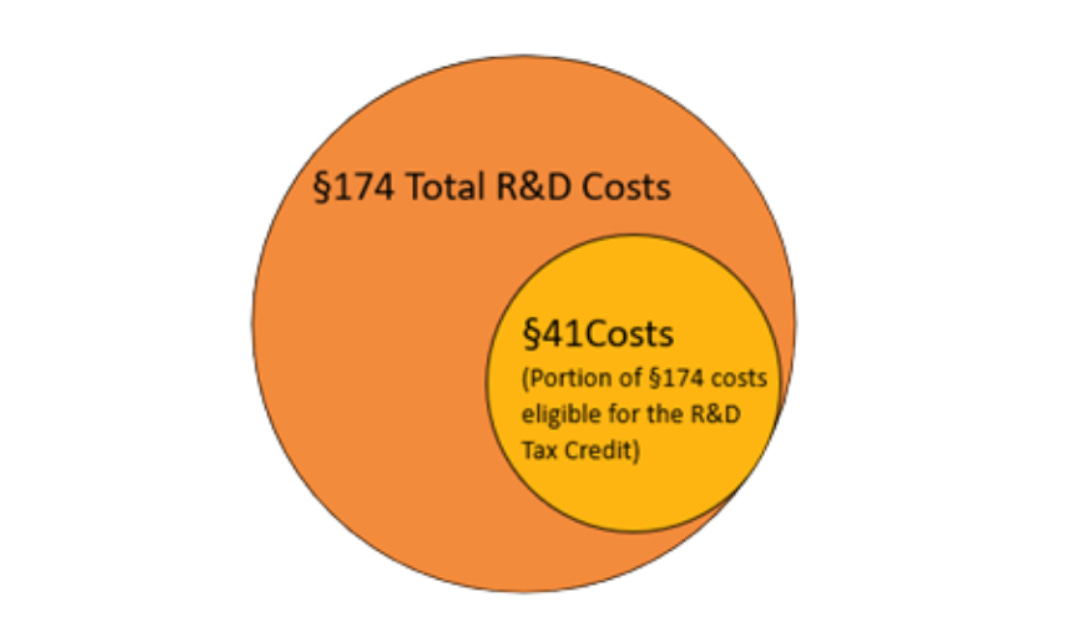

Tech companies are now forced to understand – and use – R&D credits. The S174 amendment forcibly categorizes pretty much all software development as R&D. The upside of this that R&D credits do offset the tax bill, but only partially:

Innovation across all US software companies will take a hit if Section 174 stays. The tax change incentivizes software companies without large cash reserves to invest less in research and development. Or they can just move abroad. But the change isn’t just bad for small software companies; it hurts even the largest ones – it is why Microsoft and Amazon are also advocating for its reversal. Why is forced amortization of software labor objectively bad?The concept of amortization (also referred to as deprecation) is as follows. Say you purchase a powerful server for $2,000 to serve traffic for your SaaS business. You pay $2,000 on the spot. However, the expected lifespan of this server is 4 years, after which you expect to replace it. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that you are getting about $500 worth of “value” every year from this server, and so you amortize (deprecate) a quarter of the value of this server every accounting year, until year 4. This kind of deprecation is sensible, as you could sell your server for around $1,000 after two years (assuming that is how its value deprecated.) Tax authorities in different countries have come up with deprecation frameworks that businesses follow along these lines. For example, in the US, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) created the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) provisions, which include a framework on how to deal with deprecation. Amortizing software development over years makes sense – but only in some cases. If you have launched a software product, have customers, and you can forecast demand for this product pretty accurately, then investing developer hours to keep this SaaS running feels similar to buying hardware. The software engineer could build a new feature for the SaaS which generates revenue for years to come. So there is some argument to treat software development akin to buying a server. But is comparing physical goods to software, accurate? Take a company that buys a server office it plans to use for 20 years. After a massive one-off investment, the only cost is maintenance, which is a pretty minimal cost. Now take the example of creating software to generate revenue for 20 years. If you do barebones maintenance, the software becomes obsolete in a year or two! You need to keep adding new features and keep up with the competition. As you add more features, you run into tech debt and architecture issues, so you refactor the software and within a few years you rewrite the whole thing! Building software is like continuously renovating – and rebuilding – a property. While it is tempting to see why an accountant would want to treat software development amortized like physical goods, this is simply not the reality of how software products behave, or are maintained. Before Section 174, companies could choose how they categorized software developers, and could opt into deducting costs. This is what stable and highly profitable businesses like Google have done: for software products in production (and making money) it deducted developer costs over 5 years. For pre-launch projects, Google simply expensed those developers. This is the sensible way to run a software business, after all! Will the US be content being a less competitive place for startups?All founders whom I talked with hoped Congress would revert this disastrous tax code change, given its devastating impact on tech startups. However, this has not happened – and it’s unclear if it will. Founders have been trying to get the attention of Congress: sending a letter signed by 1,000+ software businesses, and creating coalitions like the American Innovators Coalition. Another group formed in March this year is the Small Software Business Alliance, created by indie SaaS founder Michele Hansen, supported by over 600 small software company founders. I asked Michele why she thinks the general public isn't aware of the threat to US companies. She said:

Michele said there is reason for hope, though. Congress appears to have struck a deal: revert Section 174 changes on R&D expensing. Lawmakers are now looking for ways to finance this deal. One country making software development less competitive obviously benefits other countries. Thanks to the S174 amendment, starting a tech company outside the US is far more attractive – including for raising startup capital. Still, the US has long been the global innovation hub for technology, and the country kneecapping technological innovation might let the rest of the world catch up. But I cannot see this being beneficial for innovation, as a whole, globally. Thank you to Michele Hansen and Jacek Migdał for their insights and reviewing a draft of this section. This was one out of the four topics covered in this week’s The Pulse. The full edition additionally covers:

Hire Faster With The Pragmatic Engineer Talent CollectiveIf you’re hiring software engineers or engineering leaders, join The Pragmatic Engineer Talent Collective. It’s the #1 talent collective for software engineers and engineering managers. Get weekly drops of outstanding software engineers and engineering leaders open to new opportunities. I vet every software engineer and manager - and add a note on why they are a standout profile. Companies like Linear use this collective to hire better, and faster. Read what companies hiring say. And if you’re hiring, apply here: Featured Pragmatic Engineer Jobs

See more senior engineer and leadership roles with solid engineering cultures on The Pragmatic Engineer Job board - or post your own. You’re on the free list for The Pragmatic Engineer. For the full experience, become a paying subscriber. Many readers expense this newsletter within their company’s training/learning/development budget. This post is public, so feel free to share and forward it. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

The Pulse: Will US companies hire fewer engineers due to Section 174?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

I Quit AeroMedLab

Watch now (2 mins) | Today is my last day at AeroMedLab ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment