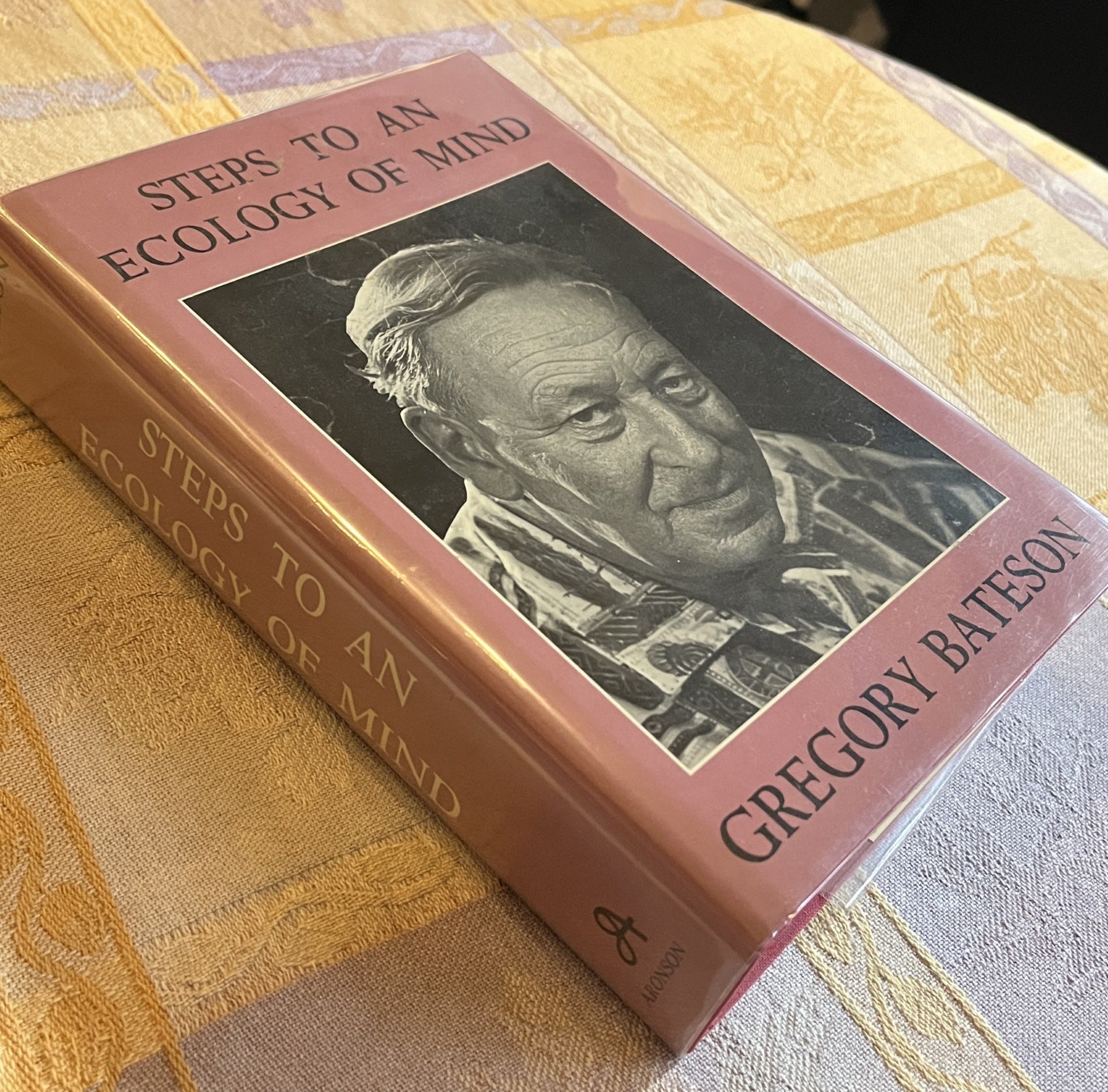

I recently shared a controversial technology reading list. I recommended 26 books, but there was a catch. All the books on the list were written by outsiders. Instead of consulting technocrats or coders or venture capitalists, I turned to the best philosophers, humanists, novelists, social thinkers, and other non-STEM visionaries. I hoped to assess today’s technology from a human perspective. And these were my guides and touchstones. At this moment in history, we need this outside perspective, It may be our only hope in the face of today’s growing wave of dysfunctional tech. The evidence is now clear and irrefutable. Technology is no longer about progress. (If you doubt me, consider this list of 52 warning signs.) I promised back in August that I’d have more to say about the wise thinkers on my tech reading list. Today I want to tell you about one of the wisest of them all—Gregory Bateson. That’s not a name you hear often nowadays. But you should. The text below draws on an essay I published back in 2020. But the questions it raises are far more relevant today. If you want to support my work, please take out a premium subscription (just $6 per month).

WHY GREGORY BATESON MATTERS(1) My Broken Dreams of a CountercultureThe counter-culture of the 1950s and 1960s is now a relic of the distant past, as quaint and charming as the hippie outfits and love beads in your grandparents’ attic. But today that whole movement feels like a dream, with less real-world impact than an LSD trip. It was an experience (to use a popular word of the era). But experiences don’t last, by definition — perhaps that’s what makes them so special. During my coming-of-age, in the aftermath of the protests and love-ins, I firmly believed that the outsiders had triumphed. We had stopped the war, overcome the censorship, and defeated the system—it would never recover. (Ah, how naive I was.) I was too young to participate in the Summer of Love or attend Woodstock. But when I reached my teen years not long after these events, I couldn’t imagine society going back to its earlier stodgy ways. You can say I was a dreamer, but I wasn’t the only one. There was a pervasive feeling that things had changed in some irrevocable manner. Surely America had now learned the futility of promoting never-ending military campaigns in remote parts of the world. It was just as obvious that crass materialism and status-seeking via possessions had been discredited. Even more, power and money had been turned into jokes and talismans of shallowness — making room for other priorities, more experiential and principled, to come to the forefront. I was certain that freedom of expression would never again succumb to the censorship and witch hunts of the 1950s. By the same token, we were too smart to continue polluting our environment and destroying our ecosystem. And who wanted to turn back the clock and give up hard-won gains in civil liberties, due process, equality, limitations on government surveillance, restraints on police brutality, and dozens of other areas of tangible progress? I’d thought the counterculture had won the battle, but that was all a mirage. Peace and nonviolence didn’t prevail. Respect and tolerance didn’t become second nature. Crass materialism did not retreat—in fact, it didn’t budge an inch. As I look back on those days with the benefit of hindsight, I have a nagging feeling that things have gotten much worse. We are angrier than ever before, more violent and self-centered, with fewer rights and responsibilities, less tolerant and forgiving, and with less consensus on how to improve the degradations—environmental, cultural, political, technological—that encroach on every side. They had some wisdom to share. Maybe we should listen again. Bateson worked at the interfaces between technology, environment, and individual psychology. And he grasped the specific dangers faced by society when these three forces are in conflict with each other.

Facebook, Amazon, and Google didn’t exist back when Bateson lived, but he would have understood with acute insight what risks their dominance brings. If he were alive today, he would have perspicacious things to tell us about a host of other problems, whether in our environment at large, our neighborhoods and city streets, or in the deep recesses of our psyches. His specialty was understanding the ways these are all linked and how changes in one sphere often start with shifts in another. Perhaps more than anyone of his generation, Bateson grasped that the revolution won’t be televised — in fact, it can’t — if the conflict is taking place in our own heads. I could call it a kind of atlas or compendium of insights from the counterculture movement. But that wouldn’t do justice to Bateson’s ability to integrate these bits and pieces, drawn from dozens of disciplines, into a powerful, holistic worldview. That’s quite an achievement, but perfectly aligned with Bateson’s background and training. His main focus was on the hidden systems that control behavior, and this had led him through one of the strangest career paths of any 20th-century thinker. If you had met Gregory Bateson at a cocktail party and asked him “What do you do for a living?” his answer would have changed dramatically over the course of his life. Let me present a thumbnail sketch of his many vocations, not just to impress you, but to show how Bateson was uniquely situated to integrate the disparate threads of the counterculture.

As I consider the cumulative impact of Bateson’s wide-ranging vocations and experiences, I reach the conclusion that this polymath was the connecting node in the mid-century counterculture. As such, he is the single best person to give a large holistic expression to its ambitions and achievements. More to the point, Bateson’s perspective is not only still relevant—something that can’t be said for many other gurus of that bygone day—but is perfectly attuned to the peculiar areas of dysfunction in our own time. He deserves to be one of the leading thinkers of the digital age. In many ways, the Internet is the ideal case study for Bateson’s prescriptions. Those who want to launch a counterculture today (I’m one of them), do well to read his work. Steps to an Ecology of Mind is a book that resists quick summary—as you might expect from an author who covered so much intellectual and physical territory in his life. But let’s extract a few of its major concerns and examine what they might tell us about our own situation. In each instance, Bateson dealt with risks and conflicts that are easy to miss because they rarely occur on the surface. They often arise from inherent conflicts between the surface and other contexts, which can be at a macro level (an ecology, for example) or a micro level (a human psyche struggling for wholeness). One of the core lessons gleaned from Bateson is that addressing problems in ways that seem direct and results-oriented often leads to failure. Consider this flawed approach as akin to a medicine that treats superficial symptoms without ever tackling underlying causes. We find this mismatch everywhere online today—it’s a trademark of the digital age. Apps manipulate behavior, but ignore both macro social effects and the micro psychic impact. They only measure (and reward) clicks. This is a recipe for disaster. (2) The Two SystemsBateson believed that one of the greatest innovations in human history is the feedback loop. He often talked about the steam engine as an analogy for healthy human interactions—focusing on the controls in the engine that check the process and keep it running at a steady pace. If this feedback loop didn’t exist, the engine would explode. When looking for similar feedback loops in human interactions, Bateson saw that they didn’t always exist, or operate in the way they should. As a result, he recognized that there were two kinds of systems: ones that relied on feedback to create stability, and others that tended to escalate and create runaway trends. In some ways, he anticipated this. Bateson taught that the resolution of a runaway process usually happens outside the process—because there are no obvious stopping points or checks within it. And that’s how the Cold War ended. The Soviet military didn’t win (or lose) the Cold War. Instead the larger context shifted—so much so that the USSR no longer existed. Bateson would tell you that these interventions are necessary when runaway systems operate without a feedback loop. In other scenarios, this runaway system could have achieved a catastrophic endpoint in a nuclear Armageddon. Environmental degradation is another obvious example of this. Unless an outside intervention occurs, the system collapses or blows up. Like the arms race, the Internet feeds on itself without any constraining feedback loop. Technocrats see this as an advantage, not a flaw. Gift subscriptions to The Honest Broker are now available.In the old days, a company might spend decades nurturing a single innovation. It took more than fifty years for some technologies (trains, electricity, etc.) to spread to the entire US. But nowadays the fastest-growing business models—whether an app or website or cloud-built service—can reach everywhere almost immediately. To describe this in Bateson’s terms, the digital overseers have fallen in love with runaway systems. And in an uncanny, disturbing way, even our day-to-day lives away from screens and digital interfaces seem to mimic this tendency, riding a wave of escalating trends with no feedback loop to keep them in check. Think of it as an array of tools built on the model of anti-virus software or a blockchain or a private chat room. But you can only create the right kinds of checks and balances in a system after you have grasped the precise points where they have been bypassed or eliminated. Bateson is still our guru in coming to grips with this. Which leads us to…. (3) Gregory Bateson’s Radical View of the Human MindThis is the strangest ingredient in Bateson’s worldview—what he meant by the word “mind.” And his quirky approach to mental processes is hardly a small matter. After all, his larger quest was an ecology of mind. Although Bateson doesn’t make this comparison, his view is aligned with Heidegger’s concept of being-in-the-world. This way of capturing the context in describing human activity allowed the German philosopher to bypass many of the paradoxes and problems created by out tendency to divide everything into subject and object. If he is correct, this means that we can transform the world just by expanding our minds—and grasping our context and environment as constitutive elements in our own sense of self. You can laugh at this, if you want. But this contextual possibility will always exists. And Bateson’s ability to articulate it is why I see him as the defining figure of the (now forgotten) modern counterculture. Bateson believed he had only made the first steps on this journey during his own lifetime and worked to enlist others to join in this mission. He cherished situations that took people out of their subjective orientations—which for him could be listening to music, ingesting LSD, or nurturing a sense of spiritual connection. But he knew that just seeking episodic relief from self-centered behavior wasn’t enough. If we exclude our surrounding habitat from our projects of self-care—in the plugged-in, screen-obsessed manner of contemporary culture—the larger systems we have ignored will eventually degrade and fail to support us. By all indications, that danger is far greater today than it was during Bateson’s lifetime. Indeed, we may be approaching an irrevocable breaking point. (4) The Double BindBateson originally developed the double bind model, the most famous concept to come out of his research, as a means of understanding dysfunctional families. But he soon saw that it could be applied to a wide range of other situations. And others have drawn on this concept in unique ways that Bateson never envisioned. Girard is perhaps the most influential exponent. But we can see its impact on everyone from R. D. Laing to Allen Ginsberg—and on fields as disparate as linguistics, political science, and literary criticism. The intensity of these situations is enhanced by the fact that they often occur in contexts where those involved must pretend that the double bind doesn’t exist. The double bind is like Fight Club—when you participate, the first rule is that you can’t mention it.

The youngster can please the mother only by accepting the role of the enemy who causes all the problems. This becomes part of a destructive daily routine. This kind of double bind, according to Bateson, is at the root of many mental illnesses. Just admitting that the problem exists will make it worse. The only recourse is denial (and psychic pain). This is the classic double bind—and some of us have firsthand experience of it. One of Bateson’s key insights was that the double bind usually takes place simultaneously in two different contexts. In the example cited, the mother’s hostile behavior takes place at one level and the explanation of the hostile behavior operates at a higher level. This is why the double bind is the source of so much humor: What makes sense at one level is absurd at another.

Each of these gets laughs by mixing up behavior and the context for the behavior. In fact, that’s the very reason why the double bind is so dangerous: Its malevolence is embedded into the structures that surround us. The system forces us to lie even when we know the truth. (5) How Do We Fix this Mess?The double bind crisis of the present day is unprecedented, at least in the context of free democracies, which depend so much on truth-telling to function properly. How can you diagnose this? The first thing you learn about the double bind is that the evidence is always indirect. Participants won’t (or can’t) admit its influence. But to the outsider, the signs are clear. The main symptom of the double bind is a persistent and structural insistence on saying things that every disinterested party can see are simply untrue. But those vocations are useful in understanding the dynamic at play here. Why do politicians or shyster lawyers or spokespersons for big corporations say things they know aren’t true? Well, the answer is obvious: These individuals are embedded in a larger structure that demands falsehood and, even worse, rewards liars for assimilating the party line with total conviction. Of course, they will never tell you that. But that’s also in the job description. We’re back to the Fight Club syndrome. There’s a lot of anger out there now, but what it accomplishes is unclear. Bateson could have predicted that. Until the structures that impose the double bind are altered, truth-telling isn’t likely to happen—or when it happens, it’s only by pure coincidence. As a result, feedback loops won’t work, and checks and balances will neither check nor balance. And in a fast-as-lightning internet age, susceptible to the runaway forces that Bateson himself outlined, those are matters of mission-critical importance. No, I’m not asking you to dust off grandma’s love beads, or hunt down grandpa’s tie-dyed T-shirts in the back of his closet. We got rid of those old fashions for good reasons. But we also ditched the counterculture—and not just the 1960s counterculture, but the whole concept of a counterculture —for something far worse. Instead of a counterculture, with its robust decentralized structures that resist authorities and power, we have settled for warring factions that seek to augment force and dominion, steamrolling anything that stands in their way. The counterculture, in a healthy system, offers a critique of power from outside—its goal isn’t running the authoritarian surveillance state, or supervising the overseas wars, or becoming shareholders in the polluting corporations. It operates outside abusive systems as a vibrant source of the checks and balances we desperately need right now. That’s the counter in the counterculture. A society without it turns into one more runaway, escalating engine, threatening at every moment to veer out of control—much like those Bateson analyzes in his studies of cybernetics. [This article is loosely based on an essay that originally appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books on July 4, 2020.] You're currently a free subscriber to The Honest Broker. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

Why Gregory Bateson Matters

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Why Gregory Bateson Matters

Or what a counterculture might look like in the 21st century ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment