👋 Hi, this is Gergely with a 🔒 subscriber-only issue 🔒 of the Pragmatic Engineer Newsletter. In every issue, I cover challenges at Big Tech and startups through the lens of engineering managers and senior engineers. If you’ve been forwarded this email, you can subscribe here. The end of 0% interest rates: what the new normal means for engineering managers and tech leadsWe’re likely to see a preference for flatter organizations, fewer managers, and a preference for the “player coach” leadership model. Some changes present new opportunities to shine as leaders.A mega-trend that is looking to change a good part of the tech industry is the end of 0% interest rates. We previously covered what 0% interest rates are, as well as:

Today, we turn our attention to how the economic environment changing for engineering managers, covering:

The end of this article could be cut off in some email clients. Read the full article, uninterrupted. 1. Fewer engineering managers everywhereA year ago, this trend of fewer middle managers began, and has kept spreading. Big Tech companies like Meta and Google and scaleups have been shedding engineering managers in an effort to flatten organizations. And it’s not just firings; last year, Meta told several managers they were welcome to take a step down and be individual contributors – or leave the company. I said at the time:

Not all companies offer an internal transition, though. When Square let go about 1,000 people recently, an insider told me there was an unusually high number of managers. Of course, not all companies follow this pattern: Lyft let go 26% of staff (1,070 people) in the summer of 2023 and 3% of those who opted into their details being shared were engineering managers. Fewer engineering managers predicts some things:

Here’s how Karthik Hariharan, VP of Engineering at Goodwater Capital, describes this shift:

2. How the EM career path is changingManagers do less hiring, and more of everything elseA major change across almost all tech companies has been the slowing of hiring; including engineering, due to a new focus on efficiency, and less access to capital. Previously, venture-funded companies and Big Tech often hired ahead of time, and bootstrapped companies did the opposite by making hires as late as possible. Decreasing recruitment is a massive change for engineering managers. This means less time spent on it, onboarding, and navigating an organizational structure that used to change often. Indeed, this is one reason engineering managers will start taking over technical program manager (TPM) roles:

Companies less consumed by growth will likely now expect engineering managers to do more stuff with their newly available capacity, like managing complexer projects, coding, doing more in product, etc. Consider a proactive approach to evolving your role. How will you allocate your additional capacity to help your organization? Figure out where you can add value, discuss with your management chain; and if it makes sense – do it! If you go passive and appear to be avoiding new responsibilities, one might be handed to you, anyway. Worst case, your role itself could come into question if the management chain assume you’re doing less than before, given that most of what you do is now beyond scope due to lower growth. Being a manager is harder than beforeDuring the “good times,” of rapid growth, being a manager is rewarding. You hire lots of enthusiastic people, get existing engineers promoted, and when the work gets too much, another new joiner brings fresh energy to the team. Time flies when things are good. Managing during a downturn is emotionally draining, with little support. When a company is doing poorly, the motivating parts of the job are fewer, like hiring, starting greenfield projects, and promoting high performers. Instead, there’s:

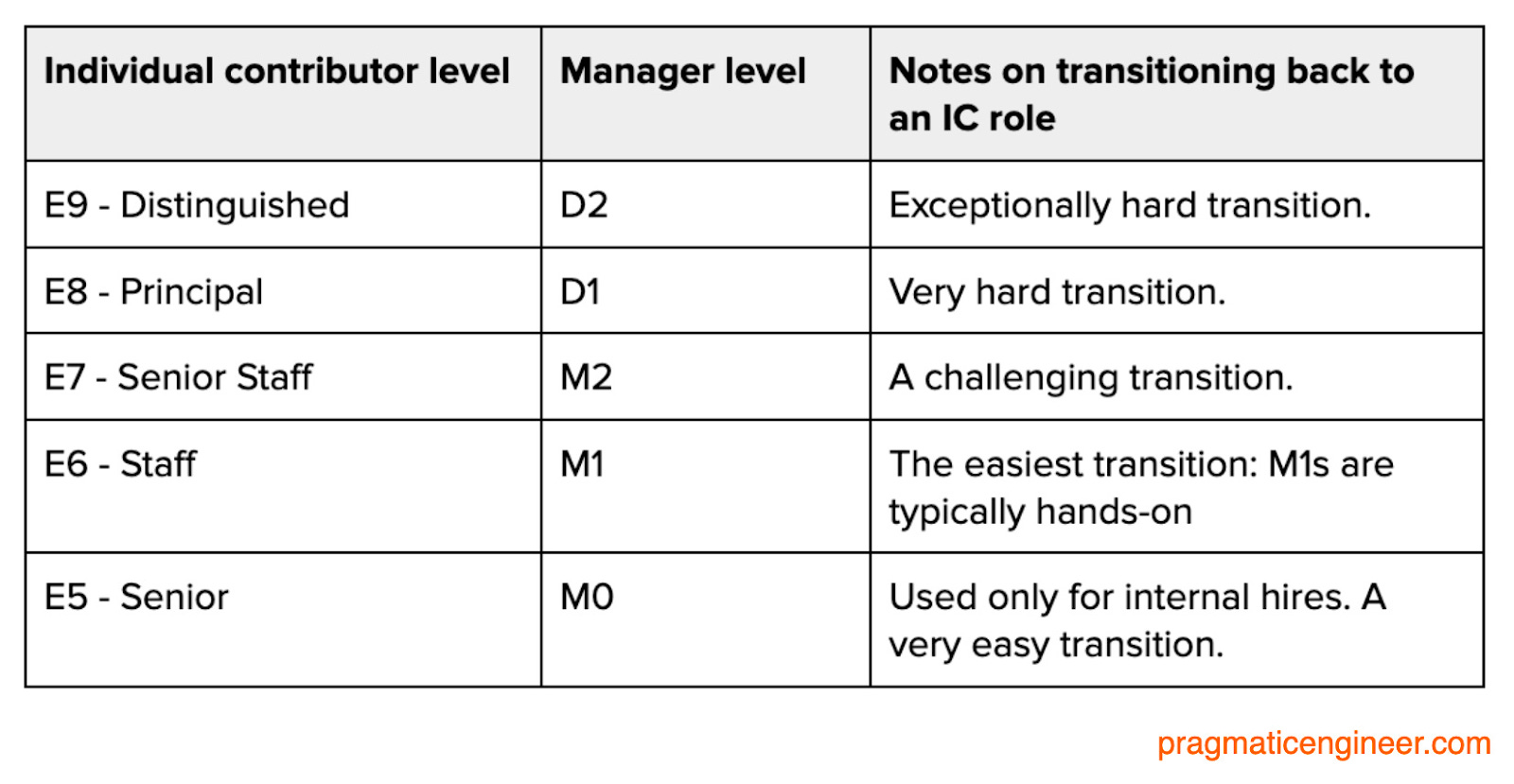

More managers return to ICs, or take a breakMany engineering managers and directors I’ve talked with are unhappy. Some disagree with decisions their leadership makes, others are disappointed about how layoffs were decided or executed, and some see their teams are shrinking, while their role isn’t the same one for which they joined the business. So, what can managers do when it’s time for a change? Get a new manager job, although the grass may not be “greener on the other side.” Two kinds of companies are hiring engineering managers, right now:

Switching to a #1 company that’s growing is what most managers would likely pick. However, there are far fewer high-growth tech companies in the current economic climate, and these manager positions at these places are highly competitive. So, if you get an offer, it’s more likely be a #2 company, one that’s perhaps struggling. Not much will be different from your old role, and it’s likely to be similarly draining. You could go back to being an IC, and act as a hands-on tech lead. This is a path I’m observing many former managers take who used to head up smaller teams. Several had titles like director of engineering or head of engineering, while working with small enough teams. A former head of engineering got “demoted” at their startup to a senior engineer position in an interesting way. They’d joined with the mandate to grow the team, but the company cut engineering budget soon afterwards, and a cofounder decided to take on managing the engineering team. The head of engineering had to either work as an engineer, or leave the company, so, a few months later, they quit for a staff engineer role elsewhere. Talking to me, they shared that they realized they really missed writing code. Plus, being an engineer means less politics and more job security than being a manager does! Take a career break. If you’re a manager at a company that has been doing poorly, including one or more rounds of layoffs, then you could be at risk of burnout. Managers have a lot of emotional work to do, but leaderships rarely offer support for this. It’s assumed managers can take care of themselves and their team – that’s why they are paid, after all! If you notice symptoms of burnout, should you keep pushing in an increasingly demotivated environment, or look for a new job? If you have sufficient savings, there could be another option: take a career break. Once you have your energy and motivation back, then get back on the job market. Engineering manager Karthik Hariharan did this; he quit his position at Roblox, and took time for himself. Then he joined a new company as VP of Engineering, re-energized, and shares this advice:

Tough job market for engineering managers unable to codeThere used to be non-tech companies that employed non-technical managers as engineering managers, but no more, reports a recent article in the finance publication, efinancialcareers:

Two interesting details in this story:

It’s a good reminder that career security as an engineering manager, is tied to staying close to where the work happens and the code is written. 3. Rise of the tech lead role and of “player coach” managers...Subscribe to The Pragmatic Engineer to read the rest.Become a paying subscriber of The Pragmatic Engineer to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content. A subscription gets you:

|

Search thousands of free JavaScript snippets that you can quickly copy and paste into your web pages. Get free JavaScript tutorials, references, code, menus, calendars, popup windows, games, and much more.

The end of 0% interest rates: what the new normal means for engineering managers and tech leads

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

The Weekender: Moon metaphors, procrastinating monks, and a visit to a cheese factory

What we’re reading, watching, and listening to this week ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ...

-

code.gs // 1. Enter sheet name where data is to be written below var SHEET_NAME = "Sheet1" ; // 2. Run > setup // // 3....

No comments:

Post a Comment